Just the other day, there was a flurry of posts on the AMS-list email list regarding Richard Taruskin’s multi-volume Oxford History of Western Music (OUP). Most of the contributors were interested in subjects that Taruskin omitted, such as Latin American composers. I am, on the contrary, unhappy with what Taruskin has put in. There are several features that we should demand in any scholarly writing, whether they be music appreciation texts, student histories or professional monographs. I will test these features through what Taruskin writes about post-war music, especially Downtown experimentalism and British experimentalism, because I know that area better than any other.

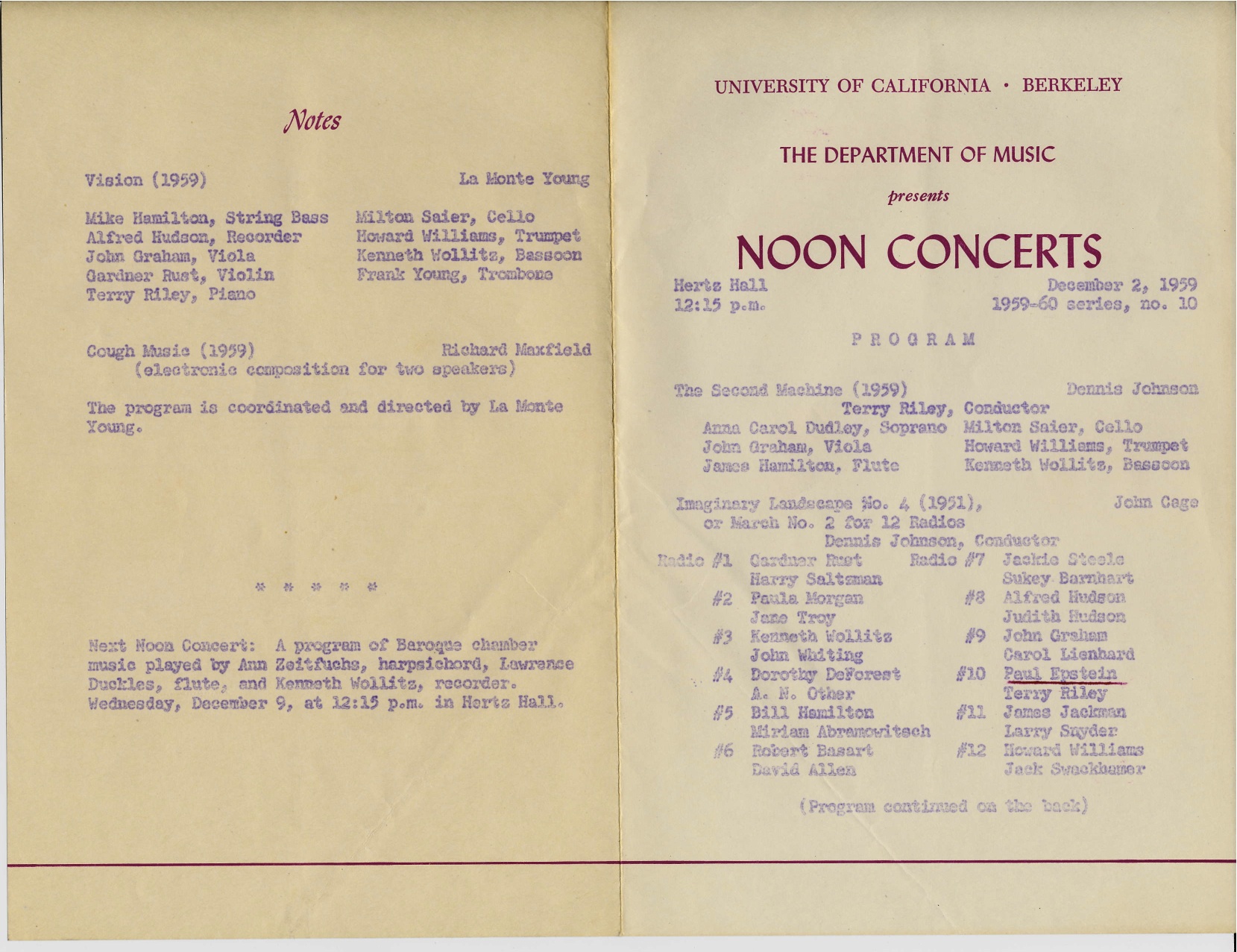

The first feature of scholarly writing is that it should be factually accurate, at least as far as its central concepts. In the section called ‘Internalized Conflicts’, Taruskin begins with a factual sentence about Cardew’s education and his work with Stockhausen. He continues, ‘In 1967 he was appointed to the faculty of the Royal Academy, but by 1969, under the influence of the Cultural Revolution instigated in China by Mao Tse-tung and his Red Guards, Cardew renounced his advanced musical techniques as “bourgeois deviationism”.’ This sentence is absolutely false: Cardew only began study of Mao in the last part of 1971. The political aesthetic of Maoist arts demands that the artwork deliver a clear message to the working classes, using the music that they understand and like. The Scratch Orchestra, which Taruskin examines in this section, uses a philosophy that is an offshoot of Cagean indeterminacy. Their work included improvisation, alternative notations, and a kind of extreme egalitarianism allowing intelligent non-musicians (and non-reading musicians) parity with those musicians trained in Western classical music. The Scratch Orchestra affected a kind of hippie-ish communality and anarchy — something quite different from the regimentation of Maoism. Most of the important ‘experimental’ music of the Scratch Orchestra, and all of The Great Learning, appeared before the summer of 1971, when the Scratch, divided by schisms, held Discontent Meetings. From these meetings here emerged a strong Maoist contingent who became increasingly important to the musical content and performance activity of the Scratch Orchestra in its political phase.

The myth of a Maoist Scratch Orchestra has been perpetuated by several critics who were hostile to Cardew and Cagean indeterminacy. They dismissed Cardew and the Orchestra, essentially, with the thought that, ‘Oh, they played rubbish and they were political extremists’. This view played well in the conservative musical and political atmosphere of British newspapers and music magazines. The clearest expression of this myth appears in entries on Cardew and the Scratch Orchestra in Norman Lebrecht’s Companion to Twentieth-Century Music (1992), which are entirely false. Taruskin does not credit Lebrecht, but he follows Lebrecht in claiming that the Scratch Orchestra broke up in 1971, another error. Instead, they moved over the next year or so to a fully political organisation performing more tonal, accessible music and turning to agit-prop theatre, political education and other areas of focus. The Scratch Orchestra stopped being a full force by 1973; they disappeared in 1974. Taruskin is writing about a group at the wrong time using the wrong musical examples.

Another feature of scholarly writing is that the writer should have explored extant research in the subject area and at least be aware of its central writings. Taruskin elsewhere cites Michael Nyman’s Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond, but here he does not use it. Taruskin instead focuses on Scratch Music, claiming erroneously, ‘For outsiders, further definition had to await the publication of Scratch Music (1972), an anthology edited by Cardew, containing examples by himself and fifteen other members of the Orchestra’. There are many other sources for information on Cardew’s work and that of the Scratch Orchestra that are available in sources such as The Musical Times. Scratch Music is a delightful collection of notes, compositions, found and newly-created art, and various other submissions by Scratch Orchestra members, arranged on the pages according to random means. It ends with ‘1001 Activities’, a list of short directions and statements that are reminiscent of Fluxus Action Scores. Scratch Music presents a rationale for the contents and a brief explanation of the Scratch Orchestra; it also contains a short article by member Michael Chant questioning whether ‘Scratch Music’ was ever a coherent Scratch Orchestra genre, and a (rather wistful) statement by Cardew that because of the move to a more politically aware aesthetic, there never be any more Scratch Music.

Taruskin nearly ignores the most useful section of Scratch Music, a reproduction of the Draft Constitution, a document which appeared in the announcement for the inaugural meeting in The Musical Times in 1969. The Draft Constitution lays out the ‘genres’ of Scratch Orchestra musical activity, including compositions, Improvisation Rites, Research Projects, Popular Classics, and a category called Scratch Music. Taruskin only looks at the category ‘Scratch Music’, treating it as if it were the entire stylistic output of the Scratch Orchestra. Along the same lines, one might describe Beethoven’s style using a collection of his piano miniatures. But there are many other elements to the output by members of the Orchestra. Scratch Orchestra compositions could be complex and multi-layered, using common-practice notation as well as text (‘verbal’) and graphic notation. Improvisation Rites and Scratch Music, on the other hand, could be short compositions, but they also could be incomplete in some way, representing notes for accompaniments (Scratch Music) or situations for improvisation (the Rites). Popular Classics were just that — any piece known well to part of the membership — and Research Projects were longer, sometimes collaborative, projects in which the research into phenomena (including illogical conclusions) fed into some kind of performance. Finally, given that Taruskin appears to believe that Cardew is the founder, leader, and main figure of the Scratch Orchestra, it is astounding that he does not deal with Cardew’s own work, particularly Treatise (his graphic score, written before the founding of the Orchestra) and The Great Learning (1968–71), largely written for and dedicated to the Scratch Orchestra.

This leads us to two more features of scholarly writing: the writer should be proficient in the theory of (or at least reading of) the music in question and she/he should be aware of how the music appears in historical context. Taruskin describes some of the pieces in Scratch Music and the 1001 Activities without knowing how they were used, not how they could be performed today. Of the former, he can only write, ‘Very few Scratch pieces employed musical notation as normally defined. Many consisted of drawings that, without oral explanation, could not readily be translated into the sort of continuous action the constitution specified. Some, however, consisted of verbal prescriptions that occasionally suggested vivid musical (or at least sonic) results’. He lists some of these without any attempt to talk about the outcome in performance, the use of materials, or anything else that would explain the events in some artistically meaningful way. The only explanation he gives is a translation for his American readers, that a ‘Gramophone’, an instrument that appears in one event, is ‘a phonograph or record-player’. As to the 1001 Activities, Taruskin writes, ‘Some, perhaps most, are entirely “conceptual” in the sense that they can be more or less vaguely imagined but not literally realized’. He does not know that the Activities were a kind of intellectual game, a collection of events that were first mentioned on the Scratch Orchestra’s tour of Cornwall and Anglesey. They appeared in the Scratch Orchestra concert in 1970, based on another genre, the Research Project, called ‘Pilgrimage from Scattered Points on the Surface of the Body to the Heart, the Brain, the Stomach and the Inner Ear’, albeit as a protest by an anarchistic sub-group of the Orchestra called the Slippery Merchants. This group timed what was then the ‘101 Activities’ throughout the main performance, playing all Activities, whether musical, physical, or conceptual.

Taruskin could have understood these activities as artistic event had he researched Fluxus Action Scores, which are quite similar, for his section on Fluxus. Instead, Taruskin quotes George Brecht’s ‘Three Telephone Events’ from Water Yam without an indication of how they are performed. He also describes an event that he attended, but he didn’t like. The image of Fluxus that Taruskin portrays is curiously absent of women, except for Charlotte Moorman (because she played topless), despite the fact that Alison Knowles, a Fluxus member, co-edited the book Notations with John Cage. Taruskin uses this book for a number of examples, but he leaves her name off the credit.

Another feature that I would ask of scholarship at all levels is that musical examples should be explained adequately in the text. They should not be only presented and named. Any pieces that are not illustrated should be described as they appear in the score. Taruskin does not explain how the Scratch Music pieces work, nor does he really describe other examples in this volume. In the Cardew section, a page from 1001 Activites is displayed, but here, too, is another error in scholarly work. This example is credited solely to Cardew, as if he wrote all 1001 events. The error could be Taruskin’s; it could be a careless sub-editor. It is, however, an error that is glaring enough that it should have been corrected. He mentions that Cage’s ‘Lecture on Nothing’ is meant for performance as well as a lecture, but he does not go further. Lacking a score example, Taruskin makes the same error in describing 4’33” as Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Nicholas Cook, and Lydia Goehr. These writers do not refer to any of the three versions of the score, nor their variants, so what they describe is not Cage’s piece, but rather David Tudor’s performance. I have written elsewhere on the other writers’ errors (‘The Beginning of Happiness: Approaching Scores in Text and Graphic Notation’, in Sound and Score (2013)). Taruskin points out that he is describing a performance, but he does not explain how, or whether, the score would offer anything more.

Taruskin concludes by pointing out that Cardew moved to ‘writing mass songs to incite popular activism’, illustrating this with some extracts from Cardew’s political book Stockhausen Serves Imperialism in which he criticizes Cage and Stockhausen. He assesses the Scratch Orchestra in this way: ‘The Scratch Orchestra came up against the perennial dilemma of maximalism: they reached the limit. As one antagonist scoffed, “How can you make a revolution when the revolution before last has already said that anything goes?”’ Putting aside for a minute Taruskin’s rather inappropriate and vague use of the term ‘maximalism’, we find that this quotation is from an interview by Barney Childs with Charles Wuorinen in 1962, in answer to Childs’ question, ‘Is there, then, really an “avant-garde”?’. Wuorinen’s objection is something that Taruskin has used elsewhere in his criticism: a kind of all-purpose dismissal of modern music. Taruskin is thus part of a trend in criticism that I would call ‘grumpy’ history, in which an individual, movement or era is revealed to be not as good as everyone might think. For Taruskin, Cage was provoking the bourgeoisie with his pieces, so he may have liked or at least expected the sabotage of Atlas Eclipticalis in New York. Taruskin then attempts to offer a sympathetic rationale for these actions. One leaves the section on Fluxus thinking that it was run by art-house bores and later that Cardew was a swivel-eyed Maoist agitator writing anarchistic pieces with his cadre. He need go no further because the material does not deserve it. Because he writes this grumpy, incomplete history, Taruskin considers himself to be an expert on Cage. And perhaps some people actually believe him to be one.

Since this is a blog entry and not a formal review I will not go further. To go further would tire me out; it’s too much like marking a student essay, and not a very good one. But it makes me wonder, if the sections I know well cannot satisfy basic criteria for useful scholarship, what happens in the sections on music I don’t know well? Suffice it to say, I find no use for the Oxford History of Western Music.