There’s been a lot of discussion surrounding David Bowie’s sudden death. Here’s a connection with Cornelius Cardew, albeit in reaction to one gross misstep that Bowie made in his life and career. Robert Worby has published a link to the Musicians’ Union reaction to David Bowie’s 1976 Nazi salute (which he denied), in which Cornelius Cardew helped draft a statement about musicians and fascism. You can find the article here, on the MU History page: http://www.muhistory.com/from-the-archive-2-mu-response-to-david-bowies-nazi-salute/

Category: Web Watch

Science and the experimental method

Virginia Anderson’s chapter for the book Experimental Systems: Future Knowledge in Artistic Research (ed. Michael Schwab) is available as a version of record on her Academia.edu page. This chapter details some ways in which British experimental composers have used real scientific methods in their work, often with fictive materials or impossible conclusions. Composers include Cardew and the Scratch Orchestra, Gavin Bryars, and Christopher Hobbs.

You can find it here: https://www.academia.edu/4903150/Whatever_remains_however_improbable_British_experimental_music_and_experimental_systems_

Differently drumming

For some months now I’ve been playing with the South Leicestershire Improvisors Ensemble, a great local British free improvisation group, and the brainchild of the drummer Lee Allatson. Lee Allatson is a true original, as can be said of most ‘frimp’ drummers (for example, AMM’s Eddie Prévost, or Derby-based Walt Shaw). But most other frimp drummers I’ve worked with either separate their activity into ‘experimental’ and more traditional work. In the 1980s, especially, Eddie Prévost used various kinds of percussion, including the AMM barrel drum, for his experimental performances, moving to his kit drum for the Eddie Prévost Quartet. Walt Shaw, a visual artist who also drums, applied visual-arts sensibilities to his work, creating an assemblage of sound sources on and around a table, much like Keith Rowe has made an assemblage of his deconstructed guitar, which created for many, the sight and sound of AMM over the years.

Instead, Lee Allatson works mostly with his leopard-skin drum kit, augmented by a host of almost steam-punk beaters and sound sources. Lee has created a series of video etudes, in which he explores many of these sound sources on his kit. The result is, like the best etudes, a combination of the educational and the artistic. You can see them here: https://vimeo.com/album/3582288/sort:date/format:thumbnail .

Here’s the most recent one, an improvisation moving into a king of “punky” beat.

And if you’re passing the East Midlands next month, come and see the South Leicestershire Improvisors Ensemble, which we lovingly know as S.L.I.E., on 4 February at Quad Studios, Leicester, from 8.30 pm. Those of you on Facebook may wish to follow S.L.I.E’s adventures here: https://www.facebook.com/SouthLeicestershireImprovisorsEnsemble/?fref=ts The current lineup includes Lee on drums; Trevor Lines on bass; Chris Hobbs on keyboards and other stuff (resonating sound sources and perhaps bassoon); Bruce Coates on saxes. I’m listed as playing reeds, but will always be found on the clarinet end of things, and we may have a guest sitting in.

4’33” on the radio

Having heard Max Reinhardt’s deeply unsatisfactory introduction to La Monte Young’s Well-Tuned Piano (to put it kindly) the other day, I approached Robert Worby’s fifteen-minute talk about Cage’s 4’33” in The Essay: Five Seismic Moments in New Music (BBC Radio 3), with hope, as he has background — form — in experimental music. And it was really pretty good. Worby talked about his own first performance (on classical guitar), and discussed the way that performance is (or should be) active, rather than passive, and the shared element of listening between performer and audience.[1] And of course he mentioned the role of the environment in the piece.[2]

Worby mentions some restrictions that I have not found in a reading of the separate editions of 4’33” (David Tudor’s reconstruction of the original Woodstock score, the time-space notated Kremen score (and its slight variant in Source, and the published Peters ‘verbal’ score), especially the Peters edition, to which he refers. Worby stressed the idea that the three movements are required in all performances, and there is no such direction. He also seemed to suggest that one had to make some kind of gesture toward playing (Tudor depressing the pedal before closing the keyboard fall; Worby fingered different chords for each section in his performance). This doesn’t appear in the scores, so it isn’t a requirement that the performer do so.[3] Finally, Worby gave his political interpretation of the piece as resistant against McCarthyism and possibly homophobia. However, this, like his thoughts on the shared listening element in 4’33”, added a very welcome analytical conclusion to his narrative.

This was, given the introductory nature of the essay, a good take on 4’33”. It is certainly better by far than some of the mis/disinformation promulgated by writers in ‘academic’ publications who have never seen the score. Factually, you might get more from Kyle Gann’s book, No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s 4’33”. Perhaps Worby got some of his information from this book, or from Larry Solomon’s long-standing web page, 4’33”. But this is more immediate, especially for a student who is new to indeterminacy. Worby makes a great story teller; it’s well worth a listen even if you’re an old hand.

You can get this essay for a limited time (I’m not sure how long) on the BBC Listen Again pages: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06tks32

[1] At the Royal Musical Association graduate student conference at Goldsmiths College in 1989, one presenter proved his thesis that 4’33” was not a composition by sitting down at a piano, starting a stopwatch, and fidgeting for the three durations given in the Peters edition. I asked, have you ever seen a proper performance of this piece? He said he had just performed it and I replied no, you certainly did not perform it, at least not correctly. The discussion entered into social and ethnomusicological connotations of silence, which was fascinating. The presenter, a young master’s student who had obviously been given poor instruction by his advisers, was mostly silent.

[2] My personal favourite performance was at the end of the Classic Masterworks of Experimental Music Festival at the University of Redlands, 1982, which I curated. The night being warm, the stage doors were open. Given that the other pieces on the concert — Terry Riley’s In C and Frederic Rzewski’s Les moutons de Panurge — were very loud, no one noticed the sounds of the outdoors until 4’33”, when the room filled with the sounds of Saturday night on campus; the stereo sounds and happy party shouts of the boys’ dorm immediately behind the hall, and, further, the shouts and cheers of a school football game. I called this sound event an Ivesian moment in my article on time and listening in experimental music, ‘(Re)Marking Time in the Audition of Experimental Music’, in Performance Research, which is available on my Academia.edu page.

[2] I simply put the cap on my clarinet mouthpiece; when we did it in a wind band performance, we suggested putting the instruments at ‘attention’ on the players’ laps, but this was a performance decision not a score response. I discuss the distinction between the exact content of indeterminate scores and performance decisions in ‘The Beginning of Happiness: Approaching Scores in Graphic and Text Notation’, in the book Sound and Score, also available on Academia.edu.

Minimalism and Postminimalism gratis

Kyle Gann’s Postclassic blog (Arts Journal) is one site I like to turn to regularly. This time, Kyle has posted his chapter from The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music. Called ‘A Technically Definable Stream of Postminimalism, Its Characteristics and its Meaning,” this forms the second of the four regional overviews of various styles of minimalism in the book, grid-pulse postminimalism. It’s well worth a read, as it corrects some misconceptions about postminimalism in some area, and expands our knowledge greatly about others. And it’s free. Free. I write again, free. The only reason this chapter, and this book, have not picked up as much of a readership is not because it’s dense or boring, but because the book was priced out of reach of all but the most well-endowed libraries.

So, enjoy! http://www.artsjournal.com/postclassic/2016/01/technically-definable-therefore-existent.html

And, while you’re at it, may I ever-so-humbly suggest the fourth chapter, ‘Systems and other Minimalism in Britain, that I wrote. There are sweet things in both of these chapters, and both are absolutely free. https://www.academia.edu/4991379/Systems_and_Other_Minimalism_in_Britain

Pritchett on Cage and Feldman, addendum

Further to our last post, on James Pritchett’s series of posts on his blog, The piano in my life, about the Cage-Feldman Radio Happenings chats…. Pritchett has just posted the final instalment, dealing with how he received the tapes of these conversations, how the gap appeared, and what happened afterward. We won’t say any more: Pritchett’s narrative is such good historiography — just a really fine story, actually — that we’ll leave it for you to read, here: http://rosewhitemusic.com/…/how-i-happened-upon-the-happen…/

Pritchett on Cage and Feldman

The other week our friend Oded got in touch, asking if we knew about a new topic on The piano in my life on the four long conversations between John Cage and Morton Feldman in 1966–7, known as the Radio Happenings. The piano in my life is a blog written by James Pritchett, and Pritchett wrote one of the best books on Cage (it’s a classic: if you haven’t read it, try the Google Books taster: here). So it’s no surprise that The piano in my life is one of our favourite blogs here at the Experimental Music Catalogue.

The post to which Oded referred turned out to be the first in a series of posts about this conversation, starting with an article in The Guardian newspaper about the conversation. Pritchett took it up from here, about a gap in the tape at a crucial point when Cage mentioned Varèse.

JC: Everyone I mentioned that thought to is also struck, because those other ways of explaining Varèse [tape is damaged at this point; sound out for 15 seconds]. Do you suppose he didn’t know what he was doing? or knew what he was doing and didn’t want anyone to know?

This 15-second gap exists in the conversation as archived on RadioOM and Youtube.

However, Pritchett had a copy of the tape that included the missing comment, and this string of The piano in my life posts reveals the background about the Radio Happenings and what was in their conversations.

When Oded notified me of the first post, I decided to wait a while, so I could provide a link to the whole story. But now that it is almost complete, it’s much too good not to share. Pritchett has yet to finish his post, which will describe how he received the full, undamaged tape in a New York Indian restaurant. I’ll update you when he does so.

Historic photo

Having had some delay due to a web server upgrade, we were unable, until now, to post a photo here that I received, thanks to Christian Wolff. Some of you may have seen this on the EMC Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/emcsystems/, which is a good source for immediate things of interest), but I wished to place the picture here, where it will have a more permanent place to live.

Here is (l-r) Christopher Hobbs, Cornelius Cardew, and Christian Wolff rehearsing Trio II for Sounds of Discovery, at the International Students House, London, 22 May 1968. This four-day concert series occurred when Christian Wolff was resident in London, about the time he was working on his Prose Pieces and, coincidentally, Cardew was creating the first Paragraph of his massive work, The Great Learning. This concert was just under a year before the Music Now Festival at the Roundhouse, London, which would see the premiere of Paragraph 2, as well as provide the basis for the Scratch Orchestra.

Some of the materials in the foreground are there for another piece. The four-day event also included the British premiere of Terry Riley’s In C, directed by Hobbs. Hobbs was, at the time, just 17, and a student of Cardew’s at the Royal Academy of Music, but Cardew brought Hobbs into the scene as an equal participant.

I was absolutely thrilled to find that Christian Wolff had this photo, and for the Dartmouth University Library to provide a copy (it is part of a current exhibition on Wolff). In these days of digital snapshots, it is easy to forget how infrequently we documented our lives on film, due to the expense (especially indoor shots, which then required flashbulbs or fancy film stock). I will add more to the context of this photo in due course, but I thought it worth showing.

New Bandcamp ‘EP’

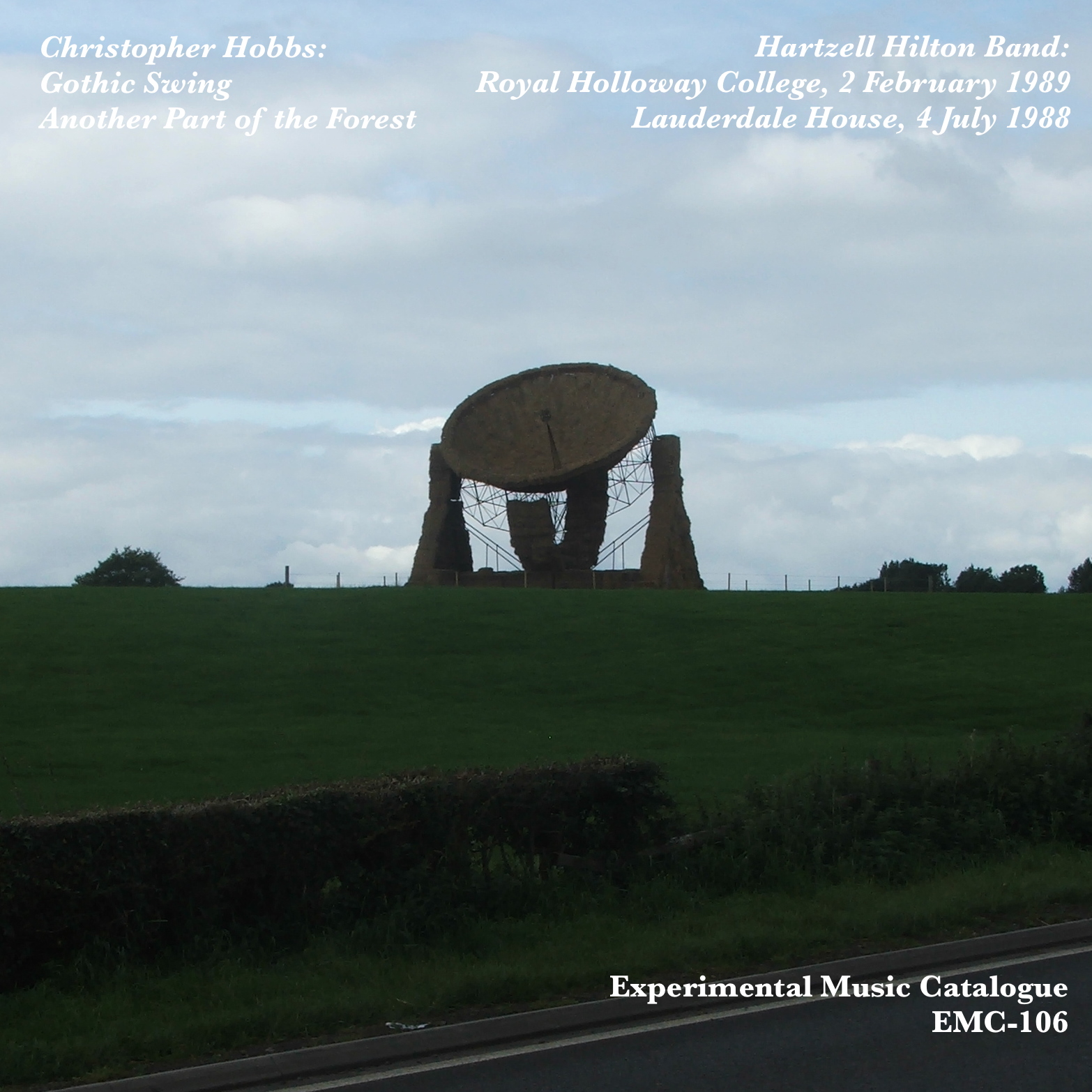

The EMC has just released their new ‘single’ download, Hobbs with the Hartzell Hilton, a set of two archival recordings by the Hartzell Hilton Band, both of pieces by Christopher Hobbs: Gothic Swing, and Another Part of the Forest.

They are available on our Bandcamp site:

http://bandcamp.experimentalmusic.co.uk/music

Here are the notes:

Gothic Swing and Another Part of the Forest were written for the Hartzell Hilton Ensemble, an idiosyncratic group which played together in the late 1980s. Its members were Jane Aldred and Virginia Anderson (Eb clarinets), Karen Demmel and Michael Newman (violas), Simon Allen (vibes) and Christopher Hobbs (piano).

Gothic Swing, recorded here in the reverberant acoustic of Royal Holloway College, Egham on February 2 1989, is an exuberant, outward-looking piece. Another Part of the Forest (recorded at Lauderdale House, London on July 4 1988) is more introspective, and while the piano plays quite an ubiquitous role in the first piece, here it is silent for almost half of the work, with the vibes providing a gentle ostinato in the long slow middle section.

Also available: our free version of Christopher Hobbs’ Sudoku 104 (EMC-105), also on Bandcamp.

Great Learning diary, pt. 2

On this post, I continue documenting my experiences preparing for the complete performance of Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning, at the Union Chapel, Islington, in July. This might be of interest for people studying notation, performance practice of indeterminate music, or for fans of the music of Cornelius Cardew. It ended suddenly, due to my inability to stand up to the sheer physical stress this amazing piece inflicts on performers. Many other performers were, however, able to work through the whole two days — many of them original Scratch Orchestra members. Well done to all of them.

Virginia Anderson

7 July:

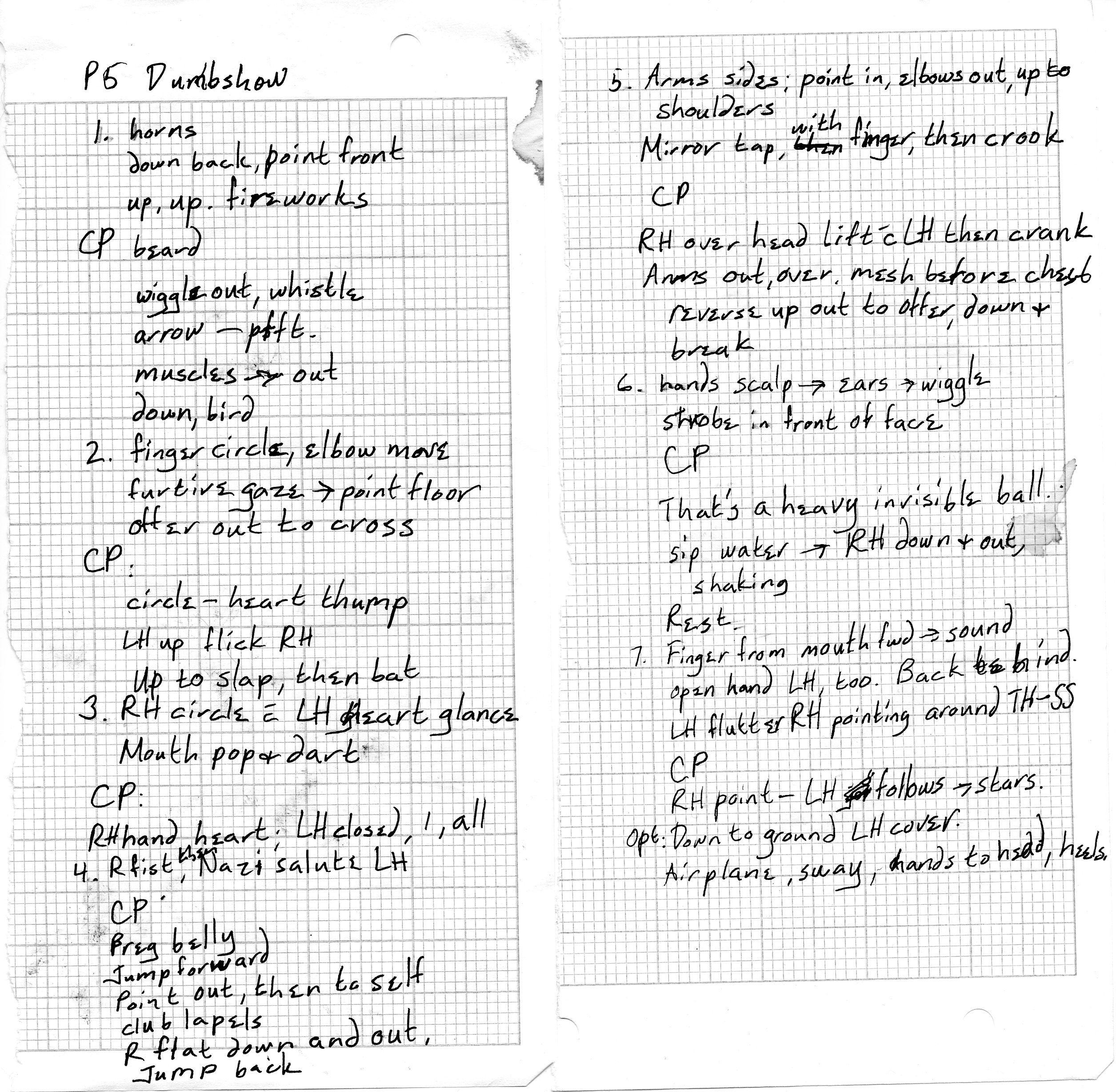

Another day, another Great Learning. This afternoon I’m down to London — Shoreditch, actually — for a rehearsal of Paragraph 4. This is the paragraph that uses a kind of alternative organology to describe the instrumentation (as in the photo yesterday). But I started with Paragraph 3, for chorus and large instruments playing a deep drone. There is something lovely and meditative about playing this drone, and something incredibly physical. My bass clarinet needs a tube to lengthen the fundamental from the normal concert B flat to A flat. The tube is much longer than one would expect; in fact, it is longer than my Selmer case. That requires a huge puff, so I’ve been lengthening my long tones from 7 to 8 to 9 to 10 seconds. This seems very short for a drone, but I’m blowing as hard as I can to get a decent dynamic. I’ve switched over to a rather light, noisy 2 1/2 Rico — not the nicest sound I can get, but it blows loud with less puff. The notes should double in length for the concert — they always do — as I get my whole-body OM in gear…. But the physicality of this paragraph and the movement of the Paragraph 5 Dumbshow are taking their toll. I may have to ask about performing a seated Dumbshow. Ah, well, on to practice the whistle solo…

7 July:

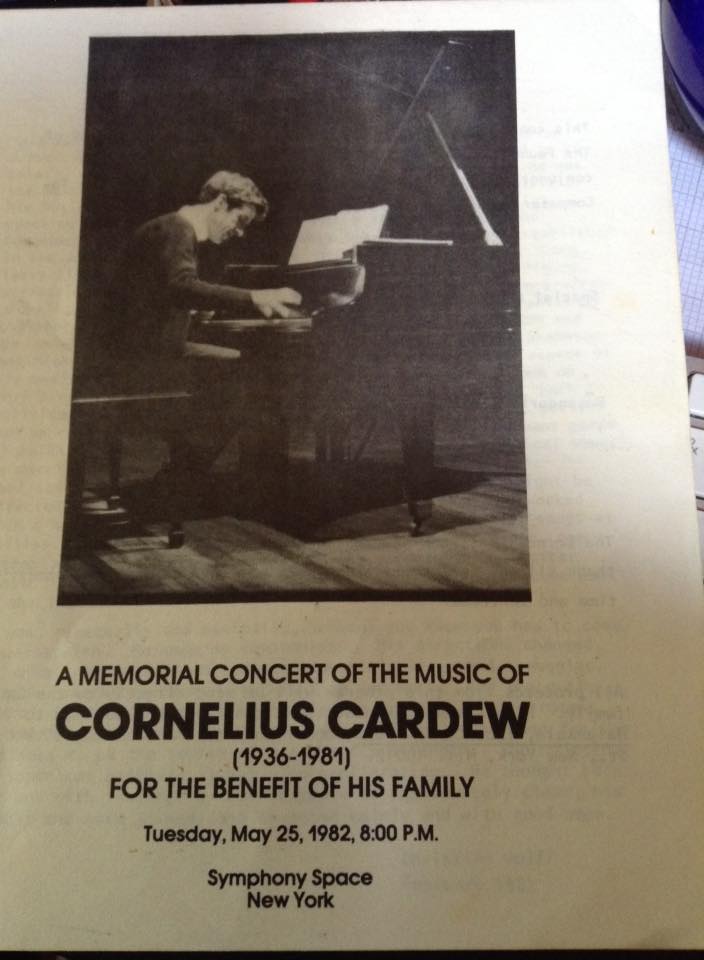

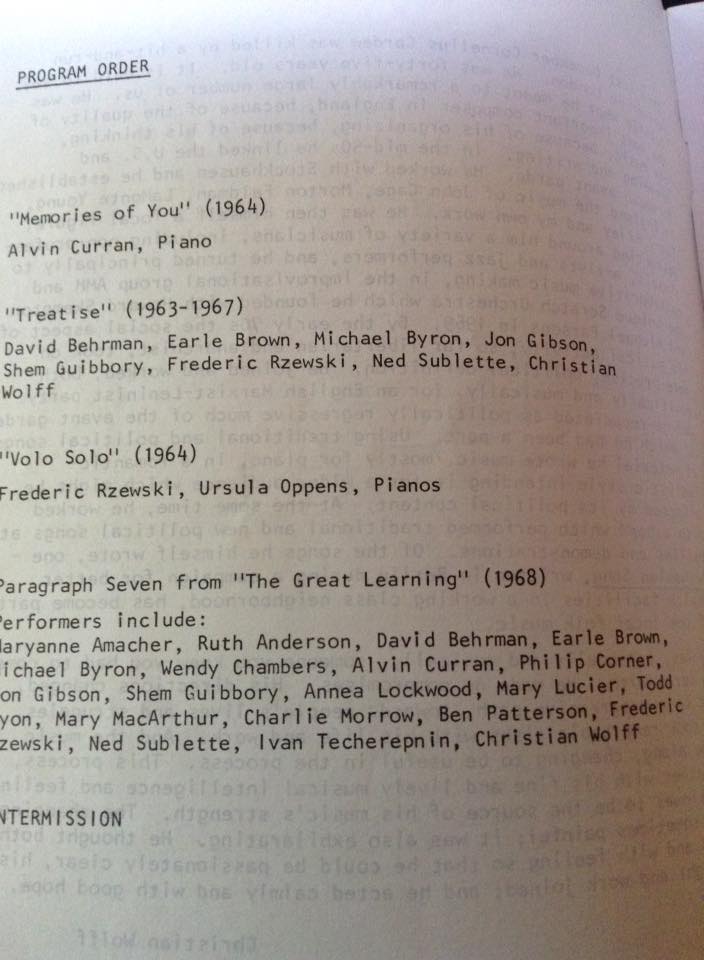

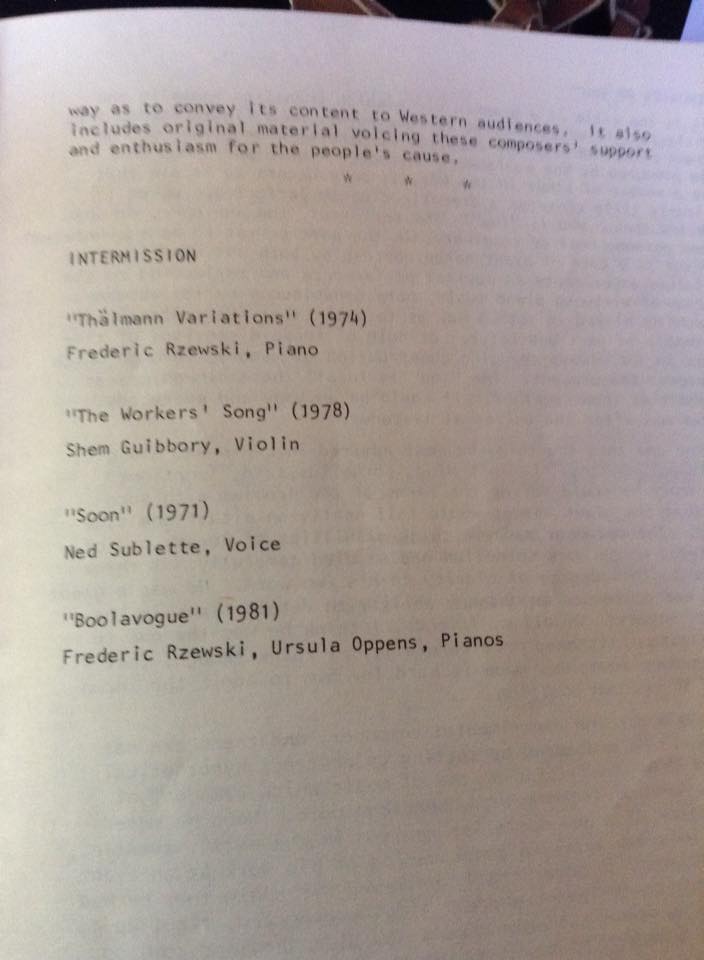

Yesterday Michael Byron mentioned performing in the New York City memorial concert for Cardew in 1982. I said that I had the programme and would look for it. Here’s just a few pages: the cover, first half and second half listing. I’ll scan these properly when I can, along with all the other pages. A star-studded line-up!

Programme, p. 1

7 July:

Just came back from a whirlwind trip to London to rehearse Paragraph 4 of The Great Learning at St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch. The group was primarily members of Coma — Contemporary Music for All. Nice people! Good singers! Dave Smith was the director. He introduced me as author of an article on Chinese characters in The Great Learning. This was my first direct experience of P4, as I laid out for it on the 1984 performance to hear it from ‘outside’, but there’s nothing like involvement. Great fun! Saw Benjamin Court [who is writing a PhD thesis on the Scratch Orchestra], who is auditing the rehearsals. My fastest London trip ever! 5 pm train, into St Pancras at 6.15, for 7 pm rehearsal, then 9.15 train to Leicester at 10.30.the cat toys are almost destroyed, but they looked and sounded good…

8 July:

Great Learning prep going apace, though at different rates. Tried one of the new bass clarinet reeds I ordered through Reeds Direct (thanks, Bruce [Coates]!) and installed the new rubber anti-vibration mat onto the mouthpiece. Wow, for the first time the Vandoren traditional bass reed worked wonderfully without breaking in! Just shows how really old and knackered my former reeds were. And the rubber thing works great. Much longer drones today 12 seconds or more with the A flat tube in. (Answered the door to a delivery guy without thinking about the tube being in — that caused a conversation!). The whistle solo moves on — I’m hearing phrasing now in my interpretation that is far better than my former efforts. The ocarina is feeling more like an instrument that I can play. The last time I played this (from the BBC recording of a performance in 1997 with the London Sinfonietta Voices), it was a bit frantic:

But the Dumbshow gestures — I can’t keep them in my head. I have a cheat sheet, but after repeated practice I can’t remember whether I’m scraping my beard, flicking dough, or trying not to make my arm look like a Nazi salute when I stick it out as required. Maybe tomorrow.

9 July:

More learning, greater learning: mostly spent today on the Dumbshow. I am beginning to remember key moves as triggers for subsequent ones. But I only have five out of six and am still consulting my cheat sheet far too often. There’s a move in Sentence 5 that, as described, will look like a Nazi salute. I’ve noticed that most performers try to avoid this through a half-raised arm. The whistle solo has taken a step back, hopefully to fly ahead (Zen and the Art of Archery has affected my practice thinking since I was assigned it to help my stage fright as a student). Whatever: hearing my old performance reminded me that the double-headed brush strokes on the whistle solo notation can be accomplished by singing and playing. Adding that, of course, had ruined the flow of the phrasing I had yesterday. In spending more time on these features, I had no time for the bass clarinet drone practice. I should do it this evening, but somehow a glass of cider found its way into my hand, to be followed by a black pepper chicken curry. Tomorrow….

10 July:

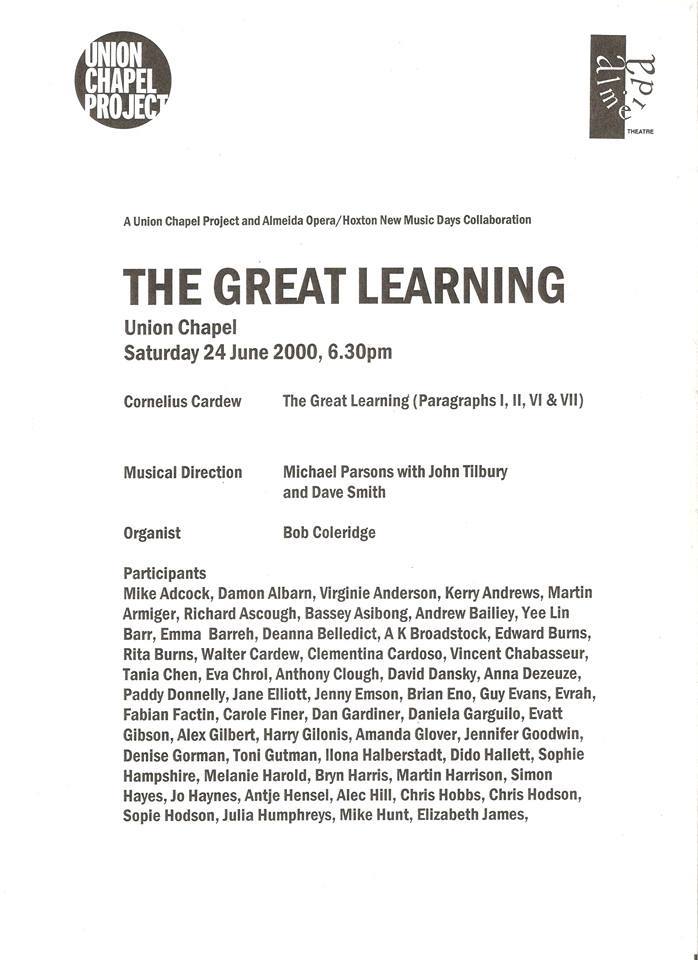

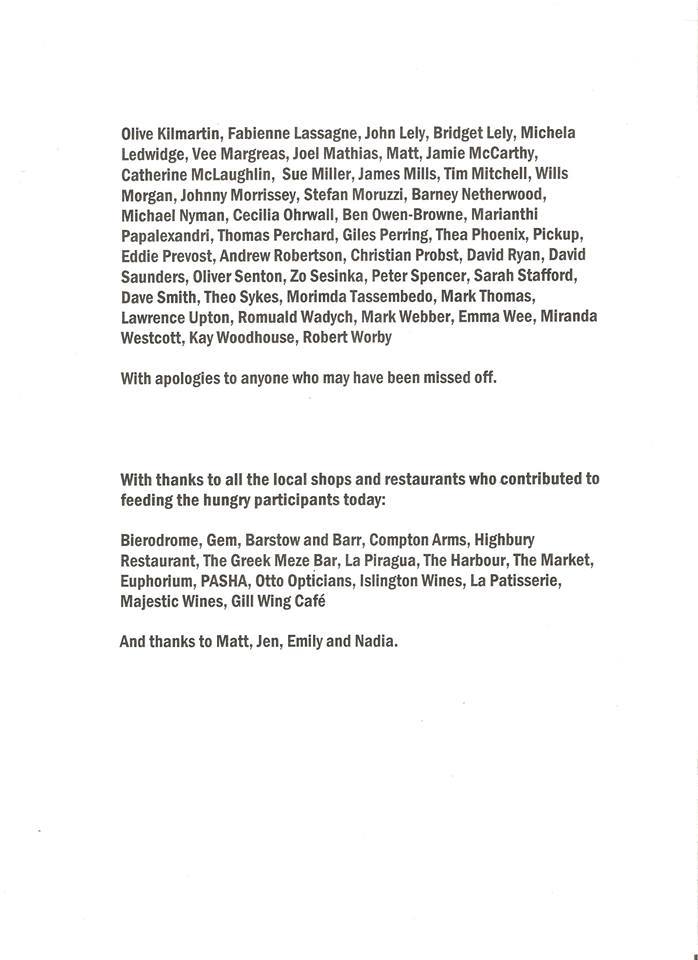

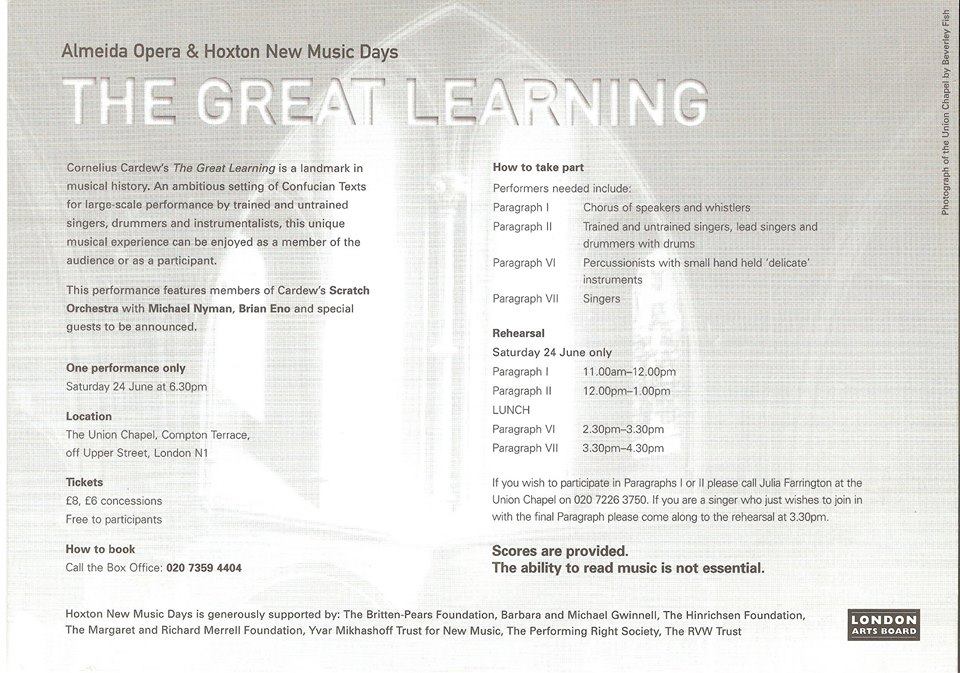

How nice that Rory Walsh sent the programme to the near-complete version of Cardew’s The Great Learning (missing out the bass-heavy P 3 and the massively long and big P 5), curated by Michael Nyman and Brian Eno. Frankly I don’t remember a whole lot about this concert — I remember Michael being there, exhorting the troops, but not Eno. I also for some reason didn’t get the programme, nor do I remember that there was a programme (Barney Childs had died the previous January and I was pretty much out of it for months). But it was in 2000 (I’d made it 1999 in another post). I do remember that P 6 was sensitively played, and that we got fed! In the 1980s we got expenses (generous ones!), in 2000 we got fed, tomorrow and Sunday we pay well over the odds for travel and anything we eat. (Hey ho). [Update: we got free drinks at the 2015 concert! well done, them!] And I remember seeing Michael Nyman with Damon Albarn of Blur, and he may have introduced us. He played in the concert, which meant that I was able to tell my pop music students that I played a gig with Damon Albarn. And looking at my (Frenchified, ‘Virginie’) name next to his, I wish I could have shown them the proof! Anyway, it’s so nice to see these. Thanks, Rory!

page 36 of weekend brochure

Programme p. 1

Programme, p. 2

Rehearsal call.

10 July:

More on the ‘Greta Larnung’: I can now get through all seven sentences of the P 5 Dumbshow with only a few glances at my cheat sheet. Of course that doesn’t mean that I’ll be that accurate on Sunday when we rehearse and perform it.

Learning the final two sentences took most of the day, along with another practice on the P1 whistle solo, which is approaching a tolerable state. I keep reminding myself that I didn’t think I could play the solo well at all when I did it for the London Sinfonietta concert in 1997. But at least I know that it’s tricky. One of the Sinfonietta Voices members decided to play a solo on a recorder head. He came up to it at the first rehearsal, giggling, like ooh, here’s some experimental music — you just do what you want, EASY! Then, realising that he actually didn’t know what he was doing, he kind of flagged, then sat down, visibly embarrassed. He did learn his part in time for the concert — that’s professionalism for you. The Sinfonietta Voices treated Paragraph 1 (on a concert with Stockhausen’s Stimmung) as a traditional dramatic reading. Christopher Hobbs has noted that each of the readings of the text (between the whistle solos) become more important, and great weight is given to the final reading, as if ‘It is rooted in coming to rest, being at ease, in perfect equity’ has transformed through adversity in the repetitions to emerge triumphant.I’ve always thought of this paragraph as being static, repetitive, ritualistic. But maybe they are holding to a tradition of performance that has always been with the early P1. Cardew wrote P1 before the Scratch Orchestra had been conceived. It was premiered at the Cheltenham Festival by the Louis Halsey Singers — all very serious modern-music concert venue and group. So perhaps the dramatic P1 is historically informed performance. However, this is not anything to do with me at the moment. As a whistler, I won’t have to do it tomorrow. Nor will Chris Hobbs, who has dredged up a pennywhistle for the drones.

A last memory about P1 in 1997. The BBC broadcast P1 and Stimmung. But they cut out two whistle solos from P1, for time. One was Chris’s, which I remember as being a cracker. This was a time when the Beeb was fighting Classic FM with the tag-line, ‘No bleeding chunks, no edits’, referring to the latter’s tendency to play only the good bits for their background-music loving Philistines. And they didn’t cut Stimmung, which, from the posh introduction, seems to have been the real great music on the bill. Typical BBC, loving the German greats, whilst ignoring their homegrown talent. And — wait for it — they didn’t announce that it was cut, thinking that no one would notice in all this modern racket. Howard Skempton was there in the audience and he listened to the radio broadcast, and he noticed. And he got angry. He wrote a stiff letter to the Beeb. Did they care? Did they, heck as like…. Now, for a quiet evening without practicing, and then two days solid of rehearsals and performance. Life should always be just like this!

10 July:

Right. Got my instruments for this weekend:

P1: pair of stones, blue ocarina

P3: bass clarinet, long cardboard tube

P4: garish pillow, deconstructed cat toy, cheese grater

P5: Dumbshow cheat sheet.I’m wondering about whether to add at least a string instrument for the P5 compositions. P2 and 7 only need my lovely voice (now, where did I put that?). P6 is being done by another group, so we can all sit and tut about how it wasn’t like that in our day. The saddest thing is that we’re leaving Eri-the-cat alone with food visits from Barbara the Cat Sitter. I hope he’ll be all right. It will be the longest we’ve ever left this guy….

11 July:

[regarding the concert announcement for The Great Learning in The Guardian (London) newspaper, which was here: http://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/jul/10/this-weeks-new-live-music ]. This announcement, by Jennifer Lucy Allen, read as follows:

‘The Great Learning, London

‘Named after Confucius’s text, radical English composer Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning is an epic work, both in terms of its subject matter and its scale. It consists of a seven-“paragraph” score, which clocks in at nine hours, and contains text performed by a large ensemble of both trained and untrained performers, who play stones and whistles, and are directed to make various movements and gestures alongside organ playing, singing and drumming. Classically trained, Cardew worked closely as a student with Karlheinz Stockhausen in the 1950s, and later became a committed and involved communist, following Mao Tse-tung and later Enver Hoxha. He was killed in 1981 after being knocked down by a car in east London. Starting tonight, the entire piece will be performed across two days by some of his close collaborators, including biographer and pianist John Tilbury’.My comment: Uh, scroll down to ‘The Great Learning, London’. There is pretty much nothing informed about this blurb. The Great Learning ‘clocks’ in at various times, including nine hours. If they only play stones and whistles, why am I filling our car with everything from bass clarinet, mbira, cat toys, bagpipe chanter….? That’s only the first paragraph. And Cardew didn’t move from being a disciple of Stockhausen to Enver Hoxha. If I saw this blurb and didn’t know the composer, I’d think it was Darmstadt bleep-bloop music combined with rousing folk songs and marches. I wouldn’t go.

11 July:

Just got done playing P1 and P2 from the Great Learning at the Union Chapel. Slight break, then P3 to follow. Great experience!

John Tilbury discussing performance strategy on P1.

Our group rehearsing P2, The Great Learning.

11 July:

P3 done. Exhausted playing those low notes, but the whole sounded good. Lots of nice feedback. Got the programme and free glass of wine. P4 starts very soon.

11 July:

Well, that’s it for the first day of The Great Learning. A long, productive day. P4 was rather good, particularly for the instruments Bryn Harris brought in: a despicable me cushion, a toy tiger wand (looking like a very long Pez dispenser, which made a noise when waved), and a fake Lego toy train as guero. Wonderful — all from the pound shop.

July 12:

I’m really sorry that Chris Hobbs and I will not be able to perform at the second day of the complete performance of Cardew’s The Great Learning at the Union Chapel, Islington. I personally found performing on four paragraphs yesterday to be so overwhelming physically that I couldn’t do the two of the remaining three and still drive home. I wish everybody my very best and hope that they have a great time, because I’m sure that P 5 and P 7 will be magnificent (as I presume P6, bagged by a group from Goldsmiths).

I’m taking away a lot from this experience. Always things that are new, and always things that are solidly old as well. Here’s one: The first picture, of Christopher Hobbs performing in a Scratch Orchestra concert at Euston Station in 1970; the second, Chris rehearsing Paragraph 2 at the Union Chapel yesterday. Same as it ever was…