This is a special treat for the EMC Bandcamp page. Rick Cox, guitarist, saxophonist, and composer, who you may know from his work with Thomas Newman on many films, for his performances with John Hassell and others, and for his recordings on Cold Blue Music, has allowed us to present Waiting for Anything, a piece written by Cox, with text by Read Miller, in an archival recording of its premiere at the Memorial Chapel, University of Redlands, in 1981, with Cox, guitar; Miller, speaker; Marty Walker, clarinet; and David Hatt, pipe organ. You can find Waiting for Anything on our Bandcamp page, here: http://bandcamp.experimentalmusic.co.uk/music . You can listen to it a number of times, and it can be downloaded for a suggested £3 (or what you will).

Here are the liner notes:

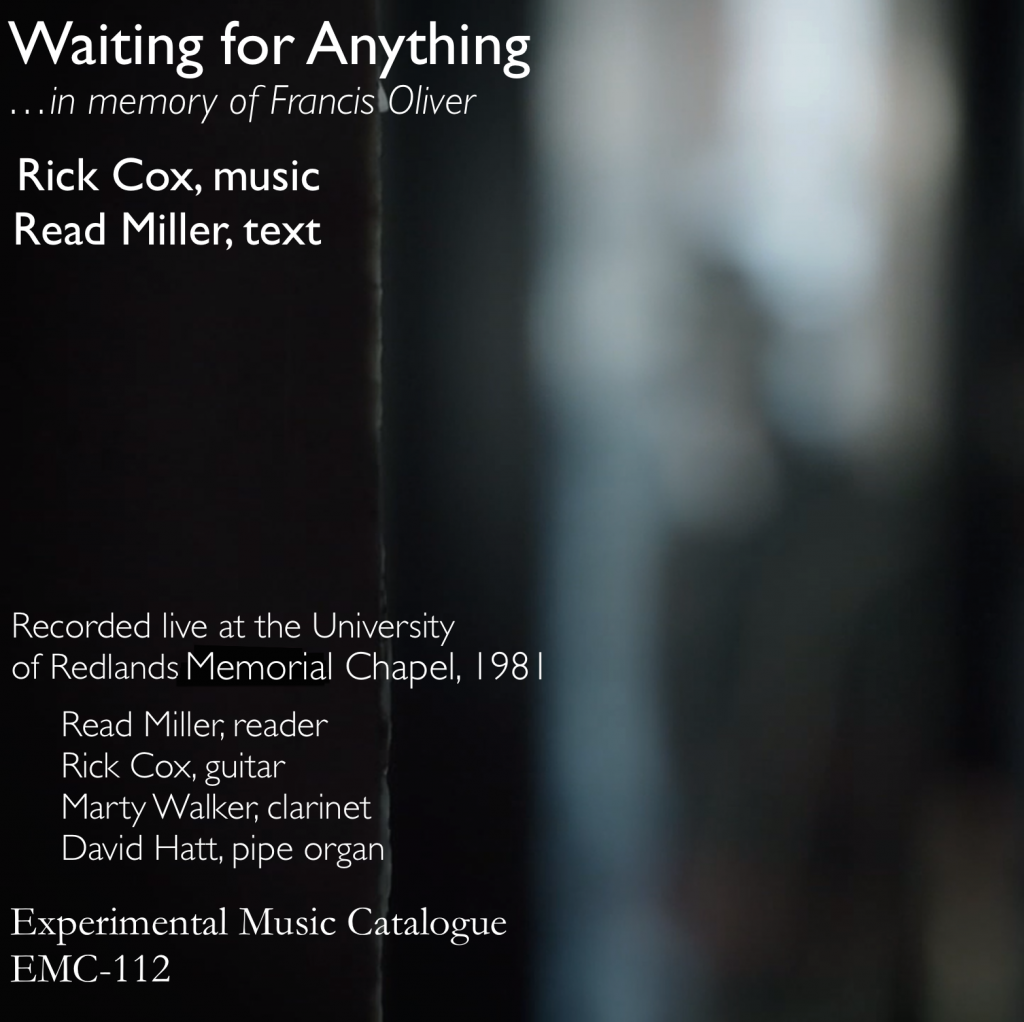

Waiting for Anything

Recorded live at the University of Redlands Memorial Chapel, 1981

Rick Cox, music, guitar; Read Miller, text, reader; Marty Walker, clarinet; David Hatt, pipe organ

Waiting for Anything was written by Rick Cox, with text by Read Miller. This, its premiere performance, was recorded live in the chapel of the University of Redlands, in memory of Francis Oliver, a former postgraduate composition student who had died that year. Waiting for Anything typifies the postminimalist style of Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly that of the artists who were based in and around the University of Redlands in the 1970s. This recording was made just before the launch of the first series of the Cold Blue label, founded by another alumnus of the University of Redlands, Jim Fox, which includes EPs by Cox and Miller.

The background to this particular performance stems from when these musicians met at Redlands, and the way that those friendships extended into the 1980s and, to an extent, today. Francis Oliver, the dedicatee, studied for a Master of Arts in music composition with Barney Childs from 1973–75, just overlapping with the arrival of Rick Cox in 1975. Oliver then moved to San Francisco. Cox had studied music with Childs at the Wisconsin College Conservatory, Milwaukee, from 1969, and had come to Redlands for further independent study with Childs, who was professor of composition and poetry at the University and its experimental institution, Johnston College. Cox was soon joined by Jim Fox, another postgraduate composition student, and Read Miller, an undergraduate poet and drummer. Fox founded the Redlands Improvisers Orchestra with Cox, Miller, and Marty Walker, a clarinetist who was part of the new music scene at the university. Another member of the new music “crowd” at Redlands was David Hatt, who had formed a duo with Walker. By the late 1970s Miller and Cox had moved to Los Angeles, where they became part of the Los Angeles hard punk, post punk, and new wave scene. In 1981 Miller and Cox were preparing to travel to New York City, where their band would have a residency, when they learned that Oliver had died of leukemia. Cox says that Waiting for Anything, and its performance in Redlands, was hurriedly arranged as a stop on their way across the country.

The recording of this performance is striking for its acoustics, instrumentation, and its construction. The University of Redlands Memorial Chapel, built in 1927, features a pipe organ by Casavant Frères, the Opus 1230, a 4266-pipe organ installed in 1928, and one of the best organs of its time in the Western United States. The Chapel was built with the organ in mind. Its acoustics especially favor the organ, as it has an extremely long delay. Although this delay muddies some group performances, it enhances the sustain and echo of Waiting for Anything, rounding out the sound of the instruments and reading. Miller’s text is evocative, referring in an allusive manner to travel and searching through a landscape. Typical of his work at this time, Miller used indeterminate procedures to arrange existing (found) texts, which give his final text a disjointed narrative. Typically, Cox used various objects to sustain and alter the sound of his electric guitar. Here it is a sponge, as can be heard in the bright, shimmering tremolo in this performance. Cox’s backing is a progression of complex chords in a cycle-of-fifths relationship. He played from memory, but he wrote Walker’s part out. Walker tended to play bass clarinet in pieces by the former Redlands composer, but here he is playing B-flat soprano. His part features slow descending notes adding to the surging and ebbing group dynamics. Hatt appeared just as Cox, Miller, and Walker began their rehearsal, so Cox quickly wrote an organ part. Hatt had studied organ at the University of Redlands before he moved to the University of Riverside for graduate study, so he knew the Casavant organ well. The organ is particularly noticeable, and effective, in the pedal notes toward the end of the track.

This recording occurred at an interesting point in the work of Cox and Miller and reflects their style at the time. Their music reflects the “pretty music” tradition of Southern California music, best known in the music of Harold Budd and Daniel Lentz. However, Cox and Miller’s work is not sweet; this recording contains a distinct and typical film noir feeling of ambiguity. The first series of extended-play 10-inch vinyl albums released in 1983 by Cold Blue Music Recordings, includes Miller’s Mile Zero Hotel and Cox’s These Things Stop Breathing. Both of these albums are nearly contemporaneous with Waiting for Anything: Cox’s album was recorded in Redlands in March 1981 and Miller’s that April. They share certain stylistic traits, including the nature of their spoken texts, with Waiting for Anything. The title track of Mile Zero Hotel also has a found, cut-up text by Miller (postcards written by a woman traveling across the country), performed by without accompaniment by Miller, Cox, and Janyce Collins. The title of These Things Stop Breathing is taken from a public safety poster about resuscitation. Its text, by Cox, is not spoken on this recording but is presented in fragments on the album art. It consists of found and cut-up fragments of breathless prose from romantic fiction. These Things Stop Breathing and Waiting for Anything also include long held notes, often with shimmering aspect (Cox’s distinctive guitar style) and ebbing and flowing dynamic surges; of simple melodies (Walker’s clarinet) and chords with muted jazz or popular connotations; and a kind of intense, though non-specific emotional content. Like other Cold Blue Music recordings of this time, Mile Zero Hotel and These Things Stop Breathing are close-miked and intimate, with a warm reverb. Waiting for Anything gains the same feeling from the natural acoustic properties of the Memorial Chapel.

Waiting for Anything is effective as a memorial piece due to its strong, though non-specific, emotional content. It had two other later performances, but Rick Cox chose this, the premiere, as his favorite, due to the acoustics of the Chapel and the raw memorial occasion of its performance. It is both typical of the music of its time and a unique piece in its own right. This is a fascinating glimpse into the state of musical life of these composers and into the history of Southern Californian postminimalism.

Virginia Anderson

Leicester, UK

August 3, 2016

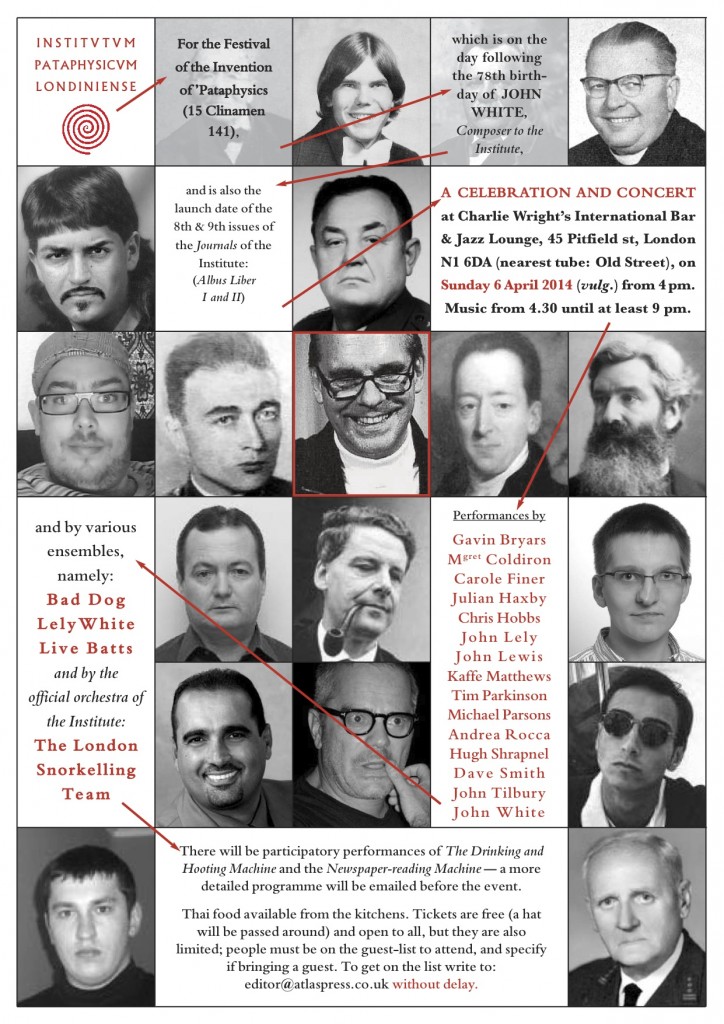

Continuing our Bandcamp theme, and continuing our Michael Parsons celebration, we’ve just uploaded a short album, called Levels. This set of three pieces were performed on Michael Parsons’ seventieth birthday concert in 2008. They consist of the title track, Levels (2007), a piece for retuned string quartet featuring the Post Quartet (Mizuka Yamamoto, Jennifer Allum violins, Richard Jones viola, Becky Dixon cello); Syzygy Duets (1991), two duets performed by Nancy Ruffer, flute, and Andrew Sparling, clarinet, arranged and extracted from an original set of eight short pieces for pairings of oboe, clarinet and two trombones; and Barcarolle (1989), a piece written for Ruffer’s alto flute, and played by her on this recording.

Continuing our Bandcamp theme, and continuing our Michael Parsons celebration, we’ve just uploaded a short album, called Levels. This set of three pieces were performed on Michael Parsons’ seventieth birthday concert in 2008. They consist of the title track, Levels (2007), a piece for retuned string quartet featuring the Post Quartet (Mizuka Yamamoto, Jennifer Allum violins, Richard Jones viola, Becky Dixon cello); Syzygy Duets (1991), two duets performed by Nancy Ruffer, flute, and Andrew Sparling, clarinet, arranged and extracted from an original set of eight short pieces for pairings of oboe, clarinet and two trombones; and Barcarolle (1989), a piece written for Ruffer’s alto flute, and played by her on this recording.