Virginia Anderson reviews Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and His Music, ed. by Renée Levine Packer and Mary Jane Leach (University of Rochester Press, 2015), in the Journal of Experimental Music Studies. See here: http://experimentalmusic.co.uk/wp/jems-journal-of-experimental-music-studies/

Category: Uncategorized

Lewis and Smith

Oh, this is a special event. In the history of British systems music piano composer/performer duos, one of the finest was the duo of Dave Smith and John Lewis. They appear prominently in Michael Parsons’ ‘Systems in Art and Music,’ The Musical Times, 117/1604 (1976), 815, and in Virginia Anderson’s ‘Systems and Other Minimalism in Britain’, in The Ashgate Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, ed. Potter, ap Siôn, and Gann (Ashgate, 2013), 87–109. So to have the two of them performing not only their duo work—the second half is a duo piece they have not performed in forty years—but also solo music by great American experimental composers and their own music. This is definitely one to attend!

Friday 2nd June 2017 6.30 pm

Schotts Recital Room

48 Great Marlborough Street

London W1F 7BB

John Lewis and Dave Smith (2 pianos)

The first half consists of a number of solos and duets including

Ives – The Alcotts

Stockhausen – Klavierstück 1

Cowell – The Snows of Fuji-Yama

Feldman – Intermission 6

Lewis – Mercury: Manganese: Magnesium

Smith – 3 Kerala song arrangements: Ethical Libertarian Scholars

The second half consists of Continuum (1970), an extended piece of early minimalism co-composed by the performers who will be performing it for the first time since 1977.

£12/£10

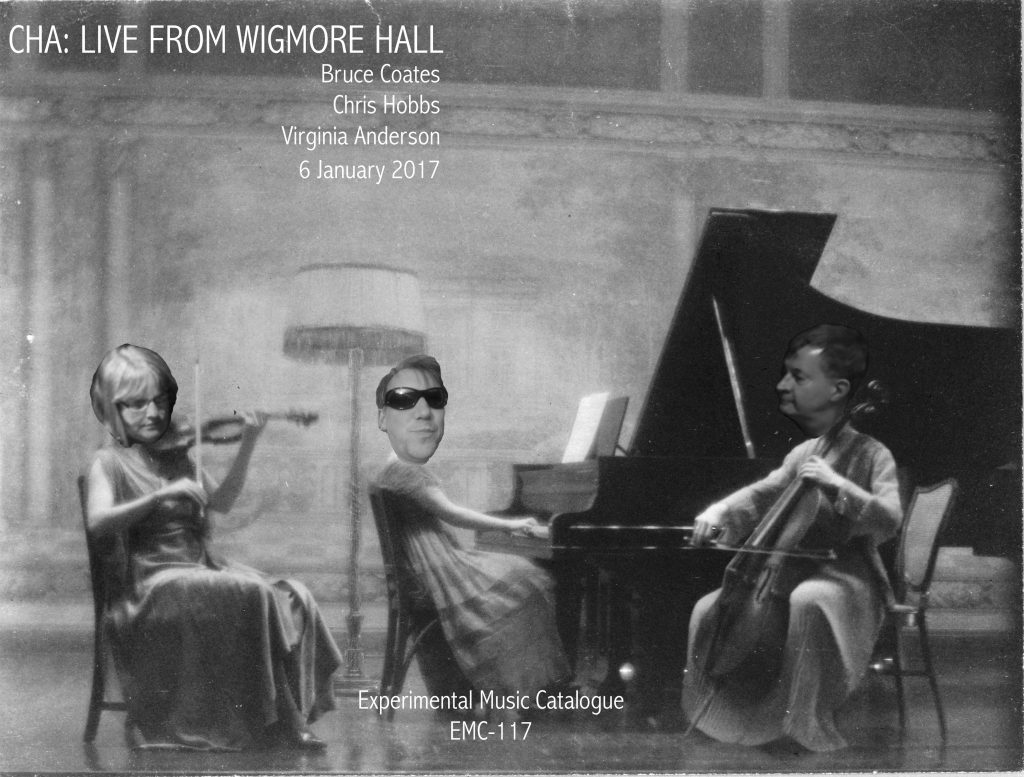

Life at Wigmore Hall

One of the most gratifying features of being on the Experimental Music Catalogue staff, and of researching British and West Coast American free improvisatory, experimental, minimal, and postminimal music, is that it is often so fun, due to an aesthetic criteria that I have described elsewhere as “humour as a noble emotion.” Instead of thinking that all good music must be weighty, scientific, made for the ages, a lot of these composers and performers, well, like to have a good laugh and use their full talents and experience to write top-quality music that is funny.

And the newest release on EMC Bandcamp from CHA (an acronym standing for Bruce COATES, Chris HOBBS, and me, Virginia ANDERSON)—CHA: Live from Wigmore Hall—began as a bit of banter. A couple of years ago, Chris Hobbs and I were driving along small country roads around Shropshire and Herefordshire, when we spotted a village sign reading “Wigmore”. Chris said, “I wonder if they have a village hall. We could play there and bill it as ‘Live from Wigmore Hall’!” This was quite a giggle: for anyone concerned with music in Britain, London’s Wigmore Hall is perhaps the premiere venue for chamber music in Britain . Built at the turn of the last century, it features stunning acoustics and hosts a weekly concert broadcast live by the BBC. Recordings issued as “Wigmore Hall Live” include works by Mozart, Beethoven, Tippett, Schubert, Britten, Brahms. To think that CHA would perform at such a bastion of classical masterworks was ludicrous. So we kept the idea in mind….

What happened—the recording, the album art, the release—has much to do with the culture of free improvisation and its “personality” and the way that CHA arose and works as a trio.

Music is Painful: The personality of free improvisation

The culture of free improvisation (meaning non-notated, usually non-tonal spontaneous performance by one or more musicians) has always seemed to me to resemble a family reunion. People assemble and interact. They may know each other well and for a long time; it may be their first meeting. Each participant brings in his or her own personality and skills to the meeting. Some players may interact with each other at their first meeting as if they had known each other their whole lives. Other players need to work with each other, to sound each other out, before they find their mix. Some players are like the favourite uncle, full of witty banter and jolly games. Some players—the free spirits—may make musical contributions that are spiritual, philosophical, or arcane (the pioneering group AMM, whose name is an acronym that is secret, has always cultivated an aura of mystery). Some players resemble an unpleasant second cousin, loudly and continuously braying out their prejudices, so that no one else can make conversation (such as the player who brought his homemade fretless bass to improvisations to make ceaseless unmusical booms). Then there are the serious souls, depicting the angst of the world both physically through their contorted bodies, and sonically. For them, improvisation is a serious business, and music is painful.

However, deep personal expression of angst is only one emotional affect that can be delivered through musical improvisation. The late Lol Coxhill was a particularly versatile performer of all sorts of free improvisation, jazz, indie popular music, and musical theatre, much of it full of delight rather than pain, and some of it laugh-out-loud funny. The Art Ensemble of Chicago, billing their concerts as “Great Black Music—Ancient to the Future” presented a panoply of styles and moods that changed from concert to concert. As one of the most “experimental” of Afrocentric bands, their use of toys, and Lester Bowie’s “scientific” experiments are perhaps closest to the experimental music in Britain that we enjoy here at the EMC. Bowie wore a white lab coat on Art Ensemble performances—a clear symbol of his role as “experimenter”. And Bowie’s exploration and ennoblement of the mundane, even tacky, corners of popular music reminds me of that great founding experimentalist, Erik Satie. His absolutely delightful album Fast Last! (1974), one of his non-Art Ensemble projects, mixed the track “F Troop Rides Again”, a meditation on the theme of one of the silliest of 1960s American comedy series, with the Broadway standard “Hello Dolly” and “Lonely Woman”, a haunting piece by Ornette Coleman. This equality of the deeply silly, the old standard, and the complex classic is reminiscent of much British experimental music since the late 1960s, especially the music of John White (whose titles and pieces can be simultaneously deep and silly), and it may lie in the deep subconscious of CHA improvisation. That is, if CHA, a spontaneous ensemble, actually stopped to think of it.

CHA: The Road to Wigmore

What CHA did think about was how to set up the joke. I found that, yes, indeed, there was a village hall at Wigmore that could be hired. So we booked a couple hours at the hall for 6 January and, on a day of flooding and pouring rain, Chris, Bruce and I met at the Village Hall. We brought our instruments, sound objects, toys and other materials. We also brought a picnic hamper filled with meat and cheese sandwiches on rye and a large bottle of Belgian beer.

This Wigmore Hall is more versatile than London’s Wigmore Hall, as it hosts keep-fit classes, meetings, and other events of interest to the villagers.

The decor is also somewhat different to that of the London Wigmore Hall, which is noted for its interior design and acoustics.

Wigmore Village Hall was decorated when we visited on 6 January with the last of the Christmas decorations. The hall’s acoustics are not bad, though unlike London, the Village Hall has no piano.

The Wigmore Hall recording

Both Chris and Bruce brought portable digital recording devices, recording in WAV format, so that there was a back-up. In the end, we used Bruce’s recording, because Bruce had better microphones. We set up the instruments, which included, for Chris, an Organetta (small reed organ), percussion, laptop with GarageBand loops, some toy noisemakers, and a radio. Bruce brought his saxophones (including a lurid plastic alto) and other sound sources, including dog toys, a metal thali, and comedy rubber animals. I brought three clarinets and stuck mainly to playing them, with only the occasional duck call.

The actual improvisation, which can be heard on the EMC Bandcamp page, is hard to describe in words. Basically, the nature of the instrumentation and the personalities of the trio gives the music a lighter, airier quality that a lot of free improv. There is more space, more short silences that many groups. And it is perhaps less aggressive than the so-called “sync or swarm” improvisation that is more commonly written about. There is a tendency toward a higher tessitura, as Bruce tends to favour his soprano and sopranino saxes, which I often match with my Eb sopranino clarinet. Chris tended to move around the room, to the dais, with its Christmas tree and his Organetta and radio; to the middle of the room, with the laptop and gong; and then carrying small percussion and his pennywhistle toward the entrance at the back of the hall. In the third set, “Consumption”, the combination of the little sax, little clarinet, and Chris’s pennywhistle set up a magnificent subharmonic drone that supported the high sounds, which, like so many subharmonics, was not picked up by the recording. Sometimes the sound world is jagged, but concords, even modality can show up. And of course, there are the toys: rubber chickens and sheep; a strange, squeaking dog toy in the form of a jack.

We decided that as much of the actual sounds that the microphones did pick up of the Wigmore Village Hall performance should be included, which is why, at the end of the first set, “Interruption”, a man’s voice can be heard. This “person from Porlock” (as Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s unwelcome visitor came to be known) wished to inform us that he and a couple other people would be using the smaller room of the hall to have a conversation. I pointed to the microphones, said, “We’re recording.” He apologized and exited. The second set, “Resumption”, and third set proceeded without further disruption, as our contented conversation at the end of “Consumption” shows. “Consumption” refers to the contents of the CHA picnic basket.

Producing the album

Bruce invented the titles after the recording and cover art had been made; indeed, after the liner notes were already in a completed draft. Titles for free improvisation tracks are perhaps the most arbitrary of all titles in music. There is no structure in free improvisation that would suggest a generic name like “sonata”; the mood or emotional “affect”, should there be one, often emerges only in real time. Many improvisers choose poetic, often obscure titles, such as “Later During a Flaming Riviera Sunset”, and “Ailantus Glandulosa” on AMM’s AMMmusic (1966). CHA has no such mystical identity: we have been primarily identified by pictures of toys (the small animal heads made by Bruce’s father, the artist Andrew Coates, which graced the promotional material for our 2013 concert at the Engine House, Manchester) or tea cups and mugs (a play on the British slang term for tea, “cha”).

This time, I wanted something that tied in with the Wigmore Hall association, so Bruce designed the cover using a copyright-free image of a piano trio of women from sometime in the 1920s. We saw, we giggled, we waited for someone to counsel for something more momentous to go with our great work for the ages, and when that objection never arose, we released CHA: Live from Wigmore Hall.

CHA, CHA, CHA….

So ends this explanation of the first CHA album. It is always a mistake to explain a joke, but since this was an in-joke between our trio, I thought I would provide some background, not just to the recording, but where it sits as experimental practice among more traditionally-minded modern music. Music does not have to be painful, though of course it can be; music can be pretty—it can be fun. I can’t wait for the next CHA adventure.

CHA live, recording in Herefordshire

Some snaps from the recording session for the new album by CHA (Bruce Coates, Chris Hobbs, Virginia Anderson), the free improv trio devoted to new sounds, fun, and friendship. This session happened last Friday in Herefordshire. We’re going through the recordings and other material just now, but we thought that you might be interested to see a cheeky pictorial hint of the proceedings. More on the EMC Facebook page, including a short video— https://www.facebook.com/emcsystems/videos/1410024602365257/ — and we’ll let you know when the album launches on Bandcamp.

On Bandcamp: Hobbs goes “spacey”!

New Release: Christopher Hobbs’ Sudoku 126 (2009), one of his Sudoku series, in which Sudoku mega puzzles determine sounds made using the Apple Garageband program. Hobbs tells it like this:

Sudoku 126 dates from 2009. It is one of a series in which long held notes, encountering each other on the same track, interact in unpredictable ways, causing wild fluctuations of pitch. In this Sudoku there are eight tracks, each containing eight notes which diminuendo over a period of four minutes. The choice of pitch and time of initiation within the track were determined by chance. The accompanying image is meant to suggest the “spacey” nature of the piece.

This Sudoku is scheduled to appear as an installation at an upcoming study day at Coventry University (more on that when we know more).

In the meantime, listen for free or download to have throughout the space-time continuum for £3 (or more if you like) for just under 40 minutes of outer-space goodness. You can find it here: http://bandcamp.experimentalmusic.co.uk/album/sudoku-126

Day music in Lincoln

Jamie Crofts, 5 Diurnes: The Brayford Pool (Lincoln) by Day

Exhibition, Friends’ Meeting House, Lincoln, Sunday, 16 October 2016 (review)

John Luther Adams, whose music has been associated with the landscape and environment of Alaska since the mid-1970s, has used the term “sonic geography” to describe “a region that lies somewhere between place and culture, between human imagination and the world around us. [in Winter Music: Composing the North (Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1004, p. 24]”. Adams’ The Place Where You Go to Listen (2008) is an installation in Fairbanks, Alaska, in which the visitor is immersed in the lights and feeling of the Northern environment, which move according to the time of day. Adams has added sound based on harmonic overtones —one, the Day Choir, and the other, the Night Choir —moving from one set of harmonics and added pulses to another with changes in light and appearance of the moon.

I was thinking about manifestations of light, activity and movement whilst viewing one of the best recent examples of sonic geography: Jamie Crofts’ project, 5 Diurnes: The Brayford Pool (Lincoln) by Day, which he launched at St Mary le Wigford, in Lincoln of 6 October 2016. I attended the second presentation of the project, at the Friends’ Meeting House, Lincoln, last Sunday, 16 October. Where composers since Field have focused on the meditative nature of night in the genre of Nocturnes (which Crofts has also done previously), and Adams seems to have balanced between day and night as one follows the other, Crofts has invented his own genre, the “diurne” in 2006. Diurnes are to day as nocturnes are to night: meditations on daytime experience. Diurnes, as Crofts explains in his notes for the piano score, are set for piano and spoken voice.

The Friends’ meeting house is a Grade II-listed building in Lincoln, itself a part of Lincoln life and history. The exhibition occurred in a secondary, Victorian, meeting room to the main 16th C. hall, and was set up with a recording of the piano part and spoken texts. The uncluttered room allowed a clear focus on the Diurnes and, perhaps, the internal pictures that the musical and verbal narrative called to the mind of the listener.

These five Diurnes focus on the Brayford Pool. This lake was used as a port by the Romans, who cut the Fosse Dyke from the River Trent at Torksey to Lincoln at the Brayford Pool, and to the River Witham, and was maintained for shipping, with improvements made in the 12th and 17th centuries. The Pool was used as an inland port as the Industrial Revolution brought manufacturing to Lincoln via the navigation canal, but as industry declined in the 20th century, the waterfront gradually moved to recreation, with one side occupied by the university, and the manufacturing giving way to number of restaurants and other entertainment businesses. The Pool is known for its resident population of swans and for an island, crowned by a weeping willow tree, which has both an obscure origin and attendant myths surrounding it.

The texts for the first, fourth and fifth Diurnes were based on a survey conducted in 2013, in which people in Lincoln were asked to complete the statement, “What I like most about the Brayford Pool is…”. Diurnes 2 and 3 were based on an article in the Lincolnshire Echo newspaper in 2010 about the Brayford Pool and its mysteries (“Is a long-forgotten secret buried beneath the island in the Brayford Pool?“, Lincolnshire Echo, 21 July 2010). Diurne 2 is distinctive in that the words (a kind of fantasy in which the protagonist wades to the island) are by Thomas Darby, while the text for the other Diurnes are written by Jim Simm (Crofts’ pseudonym). Diurne 3 poses questions arising from the newspaper article.

As Crofts told us in his rather illuminating talk after the last iteration of the 5 Diurnes, his musical scheme is based harmonically on “octonic” scales, a subset of the octatonic scales favoured by Messiaen and other composers, including John White. Like White, Crofts is interested in the music of Erik Satie, and opened his talk by showing us facsimiles of Satie’s working notes, in which he would line out bars before filling them (so that each bar was equal), set a rhythm-only system for the vocal melody (Christopher Hobbs wondered whether this was a reason that Satie’s vocal music contains so few melismas), and then filled the systems below within the grid just made. He also showed the score to Morton Feldman’s For Bunita Marcus (1985). Feldman structured his score in a kind of grid of even bars (like Satie), but then filled those bars with events in different meters and lengths (for more on the construction of this piece, see Sebastian Claren’s notes to Lenio Liatso’s recording on God Records, on Chris Villiar’s always-useful cnvill.net Feldman archive).

Crofts laid out his Diurnes in a similar manner. Rhythmic and harmonic decisions for the piano part of the 5 Diurnes were made using gaming dice. This resulted in certain core rhythms and a texture consisting of dyads to six-note chords. While Diurnes 1, 3, and 5 remain solidly in a single meter, Diurnes 2 and 4 change meter (all using the lower number 16). Diurne 1 uses, or example short phrases of this material alternated with the spoken text. Diurnes 2 and 3 bring in some processing for the voices.

The installation of recorded music and voice was broadcast from one source at the Friends House, so it was directional and demanded focus on that part of the room, but it was not a traditional concert. There was, to the side, an exhibit of the materials associated with the project: programmes, scores, and a guest book, as people were encouraged to come and go as they pleased. The score and text books are exquisitely laid out and printed. The piano part is a complete work, set in common-practice notation for performance. But the text book contains not only the text for each Diurne, but also appendices containing information, instructions, and encouragement for making unique performance versions of Diurnes 1, 4, and 5. The five Diurnes thus lie as much within the spirit of experimental indeterminacy as their fixed content lies with chance and with postminimalism. The Brayford Pool (Lincoln) by Day is an excellent, and very English, work of sonic geography. Its future performances should add richness to the piece and its perception.

*****

Note: A free ebook version of the text book is available here, with more promised on his SOUNDkiosk page. And the Bandcamp page is here.

New website

Hi there. We’ve just updated our whole site, including Jems, the catalogue, and our lovely splashpage, featuring Cornelius Cardew, Christian Wolff, and the EMC founder Christopher Hobbs, rehearsing in London in 1968, the year that Chris founded the EMC (yes, we know the strapline is ‘experimental music since 1969″, but that’s my fault in 1999…).

You’ve probably got here through that splashpage, but if you came through our old one, here it is: http://www.experimentalmusic.co.uk/emc/index.html

And have a look through it. We’re going to expand all the information on composers, performers, and others associated with the EMC, and there will be much more good stuff to read. And next up, a new Bandcamp EP of a great archival performance of a piece by Dave Smith. So…stay tuned!

Waiting for Anything

This is a special treat for the EMC Bandcamp page. Rick Cox, guitarist, saxophonist, and composer, who you may know from his work with Thomas Newman on many films, for his performances with John Hassell and others, and for his recordings on Cold Blue Music, has allowed us to present Waiting for Anything, a piece written by Cox, with text by Read Miller, in an archival recording of its premiere at the Memorial Chapel, University of Redlands, in 1981, with Cox, guitar; Miller, speaker; Marty Walker, clarinet; and David Hatt, pipe organ. You can find Waiting for Anything on our Bandcamp page, here: http://bandcamp.experimentalmusic.co.uk/music . You can listen to it a number of times, and it can be downloaded for a suggested £3 (or what you will).

Here are the liner notes:

Waiting for Anything

Recorded live at the University of Redlands Memorial Chapel, 1981

Rick Cox, music, guitar; Read Miller, text, reader; Marty Walker, clarinet; David Hatt, pipe organ

Waiting for Anything was written by Rick Cox, with text by Read Miller. This, its premiere performance, was recorded live in the chapel of the University of Redlands, in memory of Francis Oliver, a former postgraduate composition student who had died that year. Waiting for Anything typifies the postminimalist style of Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly that of the artists who were based in and around the University of Redlands in the 1970s. This recording was made just before the launch of the first series of the Cold Blue label, founded by another alumnus of the University of Redlands, Jim Fox, which includes EPs by Cox and Miller.

The background to this particular performance stems from when these musicians met at Redlands, and the way that those friendships extended into the 1980s and, to an extent, today. Francis Oliver, the dedicatee, studied for a Master of Arts in music composition with Barney Childs from 1973–75, just overlapping with the arrival of Rick Cox in 1975. Oliver then moved to San Francisco. Cox had studied music with Childs at the Wisconsin College Conservatory, Milwaukee, from 1969, and had come to Redlands for further independent study with Childs, who was professor of composition and poetry at the University and its experimental institution, Johnston College. Cox was soon joined by Jim Fox, another postgraduate composition student, and Read Miller, an undergraduate poet and drummer. Fox founded the Redlands Improvisers Orchestra with Cox, Miller, and Marty Walker, a clarinetist who was part of the new music scene at the university. Another member of the new music “crowd” at Redlands was David Hatt, who had formed a duo with Walker. By the late 1970s Miller and Cox had moved to Los Angeles, where they became part of the Los Angeles hard punk, post punk, and new wave scene. In 1981 Miller and Cox were preparing to travel to New York City, where their band would have a residency, when they learned that Oliver had died of leukemia. Cox says that Waiting for Anything, and its performance in Redlands, was hurriedly arranged as a stop on their way across the country.

The recording of this performance is striking for its acoustics, instrumentation, and its construction. The University of Redlands Memorial Chapel, built in 1927, features a pipe organ by Casavant Frères, the Opus 1230, a 4266-pipe organ installed in 1928, and one of the best organs of its time in the Western United States. The Chapel was built with the organ in mind. Its acoustics especially favor the organ, as it has an extremely long delay. Although this delay muddies some group performances, it enhances the sustain and echo of Waiting for Anything, rounding out the sound of the instruments and reading. Miller’s text is evocative, referring in an allusive manner to travel and searching through a landscape. Typical of his work at this time, Miller used indeterminate procedures to arrange existing (found) texts, which give his final text a disjointed narrative. Typically, Cox used various objects to sustain and alter the sound of his electric guitar. Here it is a sponge, as can be heard in the bright, shimmering tremolo in this performance. Cox’s backing is a progression of complex chords in a cycle-of-fifths relationship. He played from memory, but he wrote Walker’s part out. Walker tended to play bass clarinet in pieces by the former Redlands composer, but here he is playing B-flat soprano. His part features slow descending notes adding to the surging and ebbing group dynamics. Hatt appeared just as Cox, Miller, and Walker began their rehearsal, so Cox quickly wrote an organ part. Hatt had studied organ at the University of Redlands before he moved to the University of Riverside for graduate study, so he knew the Casavant organ well. The organ is particularly noticeable, and effective, in the pedal notes toward the end of the track.

This recording occurred at an interesting point in the work of Cox and Miller and reflects their style at the time. Their music reflects the “pretty music” tradition of Southern California music, best known in the music of Harold Budd and Daniel Lentz. However, Cox and Miller’s work is not sweet; this recording contains a distinct and typical film noir feeling of ambiguity. The first series of extended-play 10-inch vinyl albums released in 1983 by Cold Blue Music Recordings, includes Miller’s Mile Zero Hotel and Cox’s These Things Stop Breathing. Both of these albums are nearly contemporaneous with Waiting for Anything: Cox’s album was recorded in Redlands in March 1981 and Miller’s that April. They share certain stylistic traits, including the nature of their spoken texts, with Waiting for Anything. The title track of Mile Zero Hotel also has a found, cut-up text by Miller (postcards written by a woman traveling across the country), performed by without accompaniment by Miller, Cox, and Janyce Collins. The title of These Things Stop Breathing is taken from a public safety poster about resuscitation. Its text, by Cox, is not spoken on this recording but is presented in fragments on the album art. It consists of found and cut-up fragments of breathless prose from romantic fiction. These Things Stop Breathing and Waiting for Anything also include long held notes, often with shimmering aspect (Cox’s distinctive guitar style) and ebbing and flowing dynamic surges; of simple melodies (Walker’s clarinet) and chords with muted jazz or popular connotations; and a kind of intense, though non-specific emotional content. Like other Cold Blue Music recordings of this time, Mile Zero Hotel and These Things Stop Breathing are close-miked and intimate, with a warm reverb. Waiting for Anything gains the same feeling from the natural acoustic properties of the Memorial Chapel.

Waiting for Anything is effective as a memorial piece due to its strong, though non-specific, emotional content. It had two other later performances, but Rick Cox chose this, the premiere, as his favorite, due to the acoustics of the Chapel and the raw memorial occasion of its performance. It is both typical of the music of its time and a unique piece in its own right. This is a fascinating glimpse into the state of musical life of these composers and into the history of Southern Californian postminimalism.

Virginia Anderson

Leicester, UK

August 3, 2016

Happy Birthday, John White!

For John White’s birthday, the EMC has uploaded two of his pieces by the Hartzell Hilton Band, here: http://bandcamp.experimentalmusic.co.uk/album/wut-again-not-wut-again . But here’s some background information:

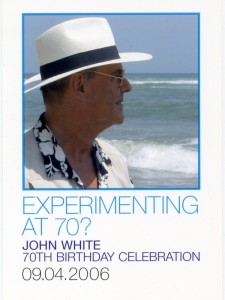

John White, now eighty, is a composer whose musical styles and interests are constantly entertaining. Born in Berlin, John was originally considering a career in the visual arts when he attended a performance of Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphonie and devoted himself to music. “Devoted” is a rather mild term. John thinks musically and works out those purely musical thoughts in a series of piano sonatas which he has kept, like a diary, since 1956. Most of the nineteenth and early twentieth-century piano composers (Medtner, Alkan, Busoni, Schumann, Satie, Reger) make appearances in his sonatas, but so too do experimental techniques, folk and pop music. This body of music alone is astounding — a marathon performance of many of these sonatas formed his seventieth birthday party at Wilton’s Music Hall in 2006 [see poster].

But wait, there’s more: for example, his theatre music, ballet and modern dance music (as music director of the Western Ballet Company and Head of Music at Drama Centre, London). John was one of the early influential composers of indeterminate experimental music; he invented systems minimalism; he was an early adopter of small digital synthesizers and computer music. Being an amazingly gifted pianist was not enough; hired by the Royal College of Music to teach composition when he graduated, John soon tired of the systems of exams and quit, teaching himself tuba to a professional standard in six months. On a pre-publication performance of Cardew’s Treatise, John chose a “perverse” interpretation, playing all rising lines as descending notes, and so on, an act that changed Cardew’s thinking about Treatise and notation. This experience led to the Machine Letters, a correspondence between John and Cardew before the premiere of John’s Cello and Tuba Machine (1968), which took up much of the first meeting of Cardew’s Experimental Music class at Morley College, London, a course that led to the formation of the Scratch Orchestra. Machines? John White invented these process systems of repetitive minimalism, using all sorts of random means — knights’ moves, dart throws, random number tables, telephone books. And if one were looking for early repetitive process music, John wrote a carillon piece using such a system in 1962. He was an innovator in several unique genres, including “Gothic” music (heavy, pounding minimalism), and, with Chris Hobbs, strict systems, in which number systems determined the note-to-note procedure in repetitive minimalism. John founded numerous ensembles: the Composers’ Ensemble, with his former students, William York and Brian Dennis; the Promenade Theatre Orchestra (PTO), with Chris Hobbs, Alec Hill, and Hugh Shrapnel; the Hobbs-White Duo; the Garden Furniture Music Ensemble, with Dave Smith, Gavin Bryars, and Ben Mason; and more, including the Farewell Symphony Orchestra, Live Batts!!!!, and Lelywhites (with John Lely).

John White is perhaps the greatest musical thinker, and the most inventive, arguably the greatest composer I have ever known. Any time spent with him is an education; any time spent with his music is a revelation. So why isn’t John White celebrated more in British music, in the world? For one thing, John never advertises himself or “bigs up” his music for career purposes. For another, his work goes against all the standards for being a big-name composer. Rather than always sticking to serious, weighty issues like most careerist composers, John’s pieces are often laugh-out-loud funny. Rather than writing the great opera or, as John called it, the “cosmological symphony”, John’s pieces can be short. He quite happily will write for instruments that are, let us say, not noble: bottles, jaw’s harps, toy pianos, tenor horn, tuba, viola, and well, my favourite, E-flat clarinet. Instead of a major university electronic studio, Live Batts!!! used the cheapest portable battery-operated synths and amps. This is one of the joys of listening to John White’s music—you will often hear instruments and instrumental combinations that “square” concert music composers would never consider. In 1985, his more formal fiftieth birthday concert had been panned by the critic Paul Griffiths, in part for what Griffiths called the “appalling instrumentation” in the Garden Furniture Music Ensemble (tenor horn, tuba, viola, and piano).

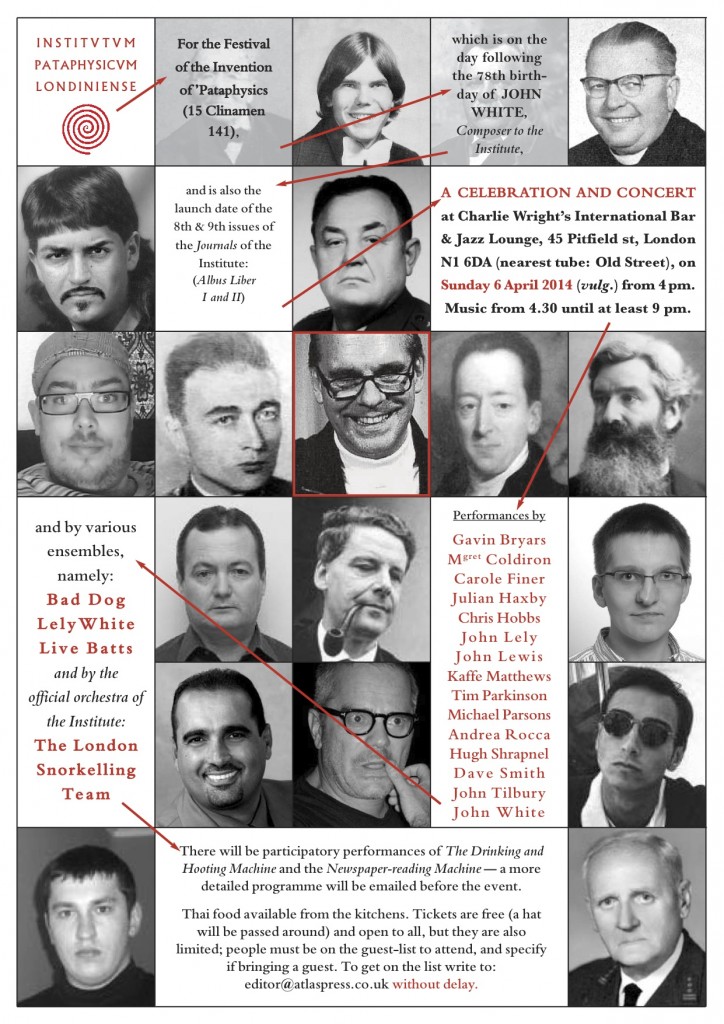

Much of John’s music recalls Satie in this respect: little pieces working out some kind of musical problem, often in the quirkiest manner. The Institutum Pataphysicum Londiniense—the Institute of ‘Pataphysics—mounted a celebration of John’s life and work for his 78th birthday, at Charlie Wright’s International Bar in London [see poster]. They also put out two issues of their journal, the Albus Liber I and II, edited by Dave Smith, to celebrate. Somehow, the venue suited John’s temperament better than the typical South Bank celebration, and the fact that they chose 78, rather than 80, for the big party was also fitting, because John does things differently. And in being different, there lies what is interesting, fascinating, thought-provoking, and fun.

*******

In celebration of his eightieth birthday, we have uploaded two pieces onto our Bandcamp page that John White wrote for the Hartzell Hilton Band: WUT Again? and NOT WUT AGAIN! (no way, shitface!). And here’s a story. The Hartzell Hilton Band came about when I met Jane Aldred, when she was playing E-flat clarinet at the South Bank for a birthday celebration for the composer Paul Patterson—just the kind of “normal” birthday concert a “serious” composer should have. We got to talking about how we loved playing E flat, and the way that it wasn’t featured on this concert for its unique timbre. Two friends, Michael Newman and Karen Demmel, played viola. I really wanted to go one step farther. E flats and violas: they seemed like the perfect chamber music ensemble, the next step forward from the string quartet! We added Chris Hobbs on piano, and Simon Allen on vibes and other percussion. We asked a bunch of composers to write for our group, including Michael Parsons and John White.

John had already written two pieces, called WUT? and Not WUT. In those days I talked to John a lot on the phone and in person and house-sat when he and his then-partner, Pat Garrett, went on holiday, so I heard quite a bit about John’s music and musical thinking. The WUT actually came from a direction in Mahler, “mit wüt”, or “with rage”. But at the time a variant of the Los Angeles “Valley Girl”, the “Essex Girl”, had sprung up, a forebear to most current reality shows. I cannot remember whether John had imagined what such a creature would make of “mit wüt” in her Estuary English, or whether he had such a student, but the response to this direction was, “with WUT?”, pronounced, as we put on the programme, to rhyme with “butt”. WUT Again? has elements that are consistent with WUT?; NOT WUT AGAIN! is, like Not WUT, an un-WUT-like piece. But there is more to this wordplay. The exclamation point and all-caps in NOT WUT AGAIN! arose from a conversation we had while John was writing the piece. I thought that it could be a cry of exasperation at yet another WUT piece: “WUT…again?” and “Oh, not WUT again!!”. This name then somehow got entangled with another topic of our conversation, American slang. John liked American slang. We had gone through some of the intricacies of certain phrases (Jack Shit? Does anybody have any, if you ain’t got Jack Shit?). One of them was the incredulous interjection, “No way, shitface!”, so John tagged that onto the title. John generously dedicated these two pieces to me and the Hartzell Hilton Band.

And that’s what we’ve uploaded, the 4th of July concert at Lauderdale House in 1988. I had advertised the concert with the fake-cowgirl promise that yee-haw, we’d be celebrating Independence Day by not playing any American music (we played a piece by Barney Childs, but he was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, so he didn’t count as American for the day). You can hear the pieces, so there is no need to go into them in detail, other than they are really lovely, and fun to play. WUT Again? has an unusual eight-bar rest — the track hasn’t dropped out, before recommencing with what turns out to be the coda. This rest is performed, or was performed by us being still and in performance mode, before the cue to resume. It’s deeply effective. Just after John wrote this piece, the earlier of the two Hartzell WUTs, I attended a composition workshop at the Huddersfield Music Festival. The leader of the group berated a composer for putting in a three-bar rest for the whole ensemble. I found this amusing and, in the general discussion of the piece, offered the example of WUT Again?, suggesting that perhaps the composer should put in a longer rest in his piece as well. NOT WUT AGAIN! (no way, shitface!) opens with the kind of action music that John had equated with radio serials such as Dick Barton, Special Agent (there is one such passage in one of his little Symphonies). This is absolutely one of the loveliest things for an E-flat clarinet to play, and is followed by a shift to the most gorgeous aspirational passages in John White’s work. It’s like the sun rising. Is this ironic as well? I prefer not to ask and instead enjoy the irony that something as beautiful as this has such a silly title. Now go listen to these pieces, here: http://bandcamp.experimentalmusic.co.uk/album/wut-again-not-wut-again Transferred from a cassette recording, they are not as “clean” as the pieces deserve, but they represent the occasion very well. And, speaking of occasions, Happy Birthday, John! and many, many more!

News from Ghent….

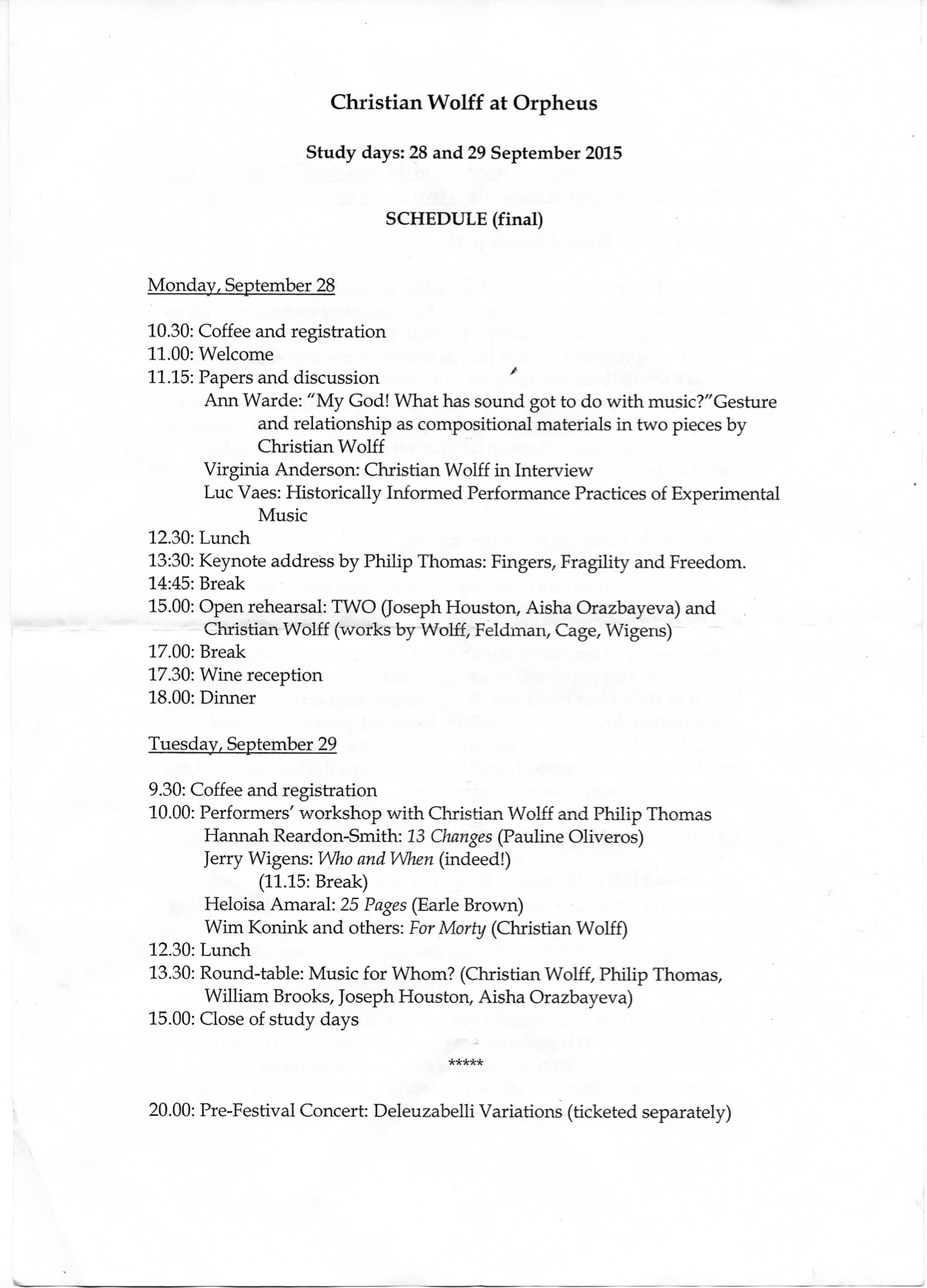

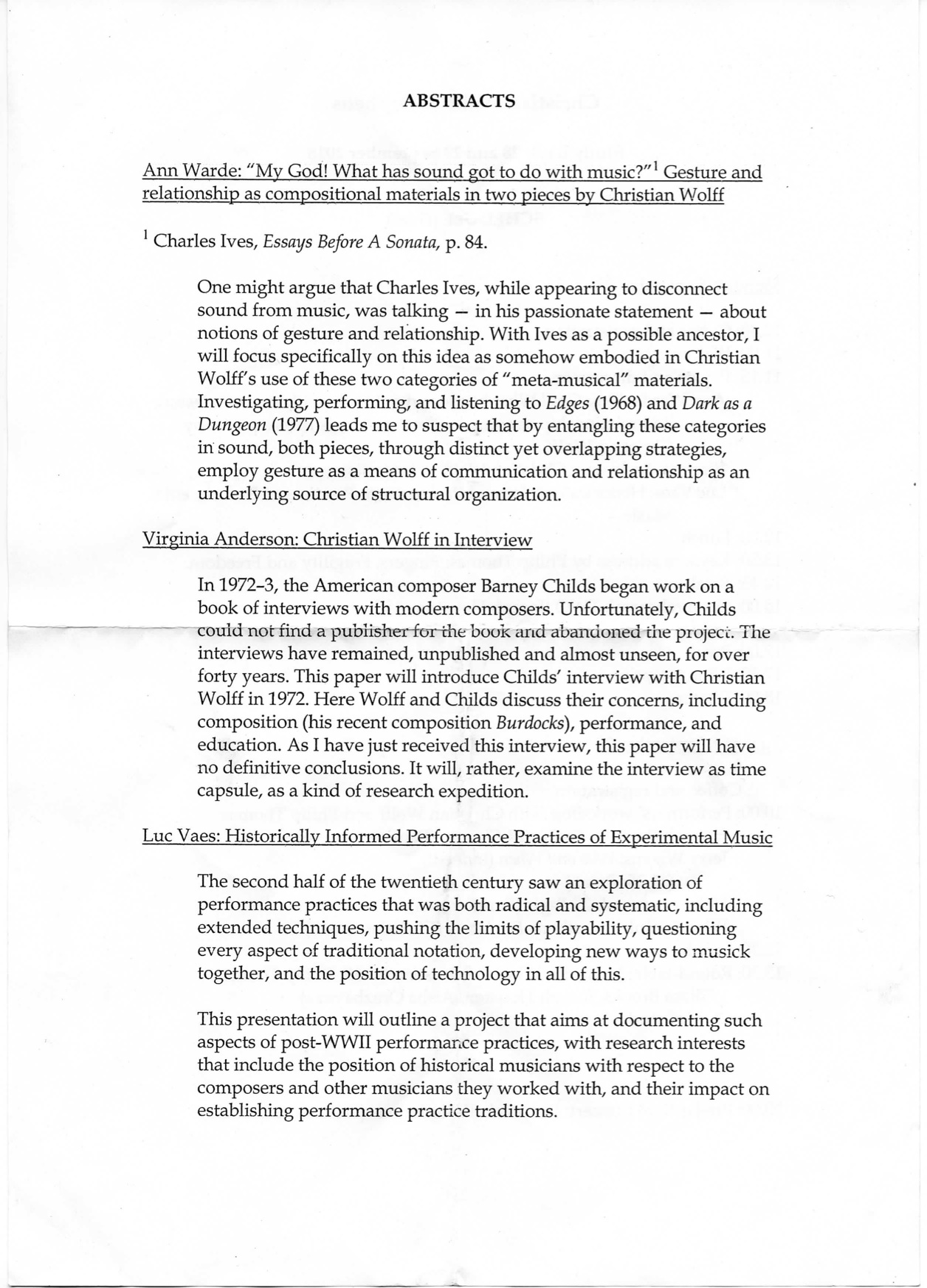

Here are some pictures and impressions from the Christian Wolff at Orpheus Study Days, 28 and 29 September at the Orpheus Research Centre, in Ghent, Belgium, as promised (before our host upgrade slowed things down…). The show started off a bit late — Eurostar from London was delayed because thieves had stolen track cables in France — but it was jolly and productive, in the way that Orpheus study days are. Our host for the proceedings was the composer and historian William Brooks, and the guest for the proceedings was Christian Wolff, himself. Although there were papers and discussion, there was a lot of time given to the performance of Wolff’s music by several very talented young professionals and students. This reflects the Orpheus goal of Artistic Research, using performance as part of the research whenever possible.

The first session contained the formal papers. Ann Warde, a Fulbright recipient from the US, resident in York University, took structural elements, especially durations, to examine the similarities in sound organisation between two very different Wolff pieces (Dark as a Dungeon and Edges). My paper, as can be seen in the abstract, dealt with a 1972 interview with Wolff by the composer Barney Childs, focusing on Wolff’s then most recent project, his large-scale experimental work Burdocks. Luc Vaes’ paper was not on Wolff, per se, but was a welcome look into performance practice of indeterminate music, focusing on the music of Mauricio Kagel.

After lunch, and the keynote address by Philip Thomas, TWO (the pianist Joseph Houston and the violinist Aisha Orazbayeva) put themselves up for scrutiny from the assembled delegates and the composer, in their performance of his work. Orazbayeva was particularly interesting as a performer, having ‘given up’ vibrato some time ago. Her tone is thus ethereal, almost folklike.

The afternoon was followed by a lovely wine reception and dinner at a local establishment.

The morning session contained more performances, including a rather stunning performance by the flautist Hannah Reardon-Smith of 13 Changes by Pauline Oliveros, and an exercise in directed improvisation by Jerry Wigens.

The afternoon saw a kind of wrap-up of ideas regarding performance and the social factor in Wolff’s music.

I have purposefully omitted to apply any critical judgement on the event because I think it should stand alone here. Almost all of the two-day event was eminently useful and highly enjoyable. Meeting Christian Wolff again was a personal highlight for me and, in many ways, personally moving. The event elided into a larger Orpheus festival which by all accounts was lovely (I was unable, sadly, to attend). But these two days provided a small-group setting in which we all had the leisure to interact with the performers, the scholars, and with Wolff himself.