In the weeks leading up to the performance of the complete version of Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning, I wrote of my experiences of preparation on my Facebook timeline. I had considered this just a report of my daily life for my friends’ amusement, but since then I have been asked to provide these notes for a wider audience. There are several performances of the complete cycle in the works, worldwide. And I’ve noticed over the years that people who have never played indeterminate music don’t know how much responsibility is placed on the performer, and how much work it can entail. So, without extra comment, here are a few things I thought about before playing The Great Learning.

June 9 2015:

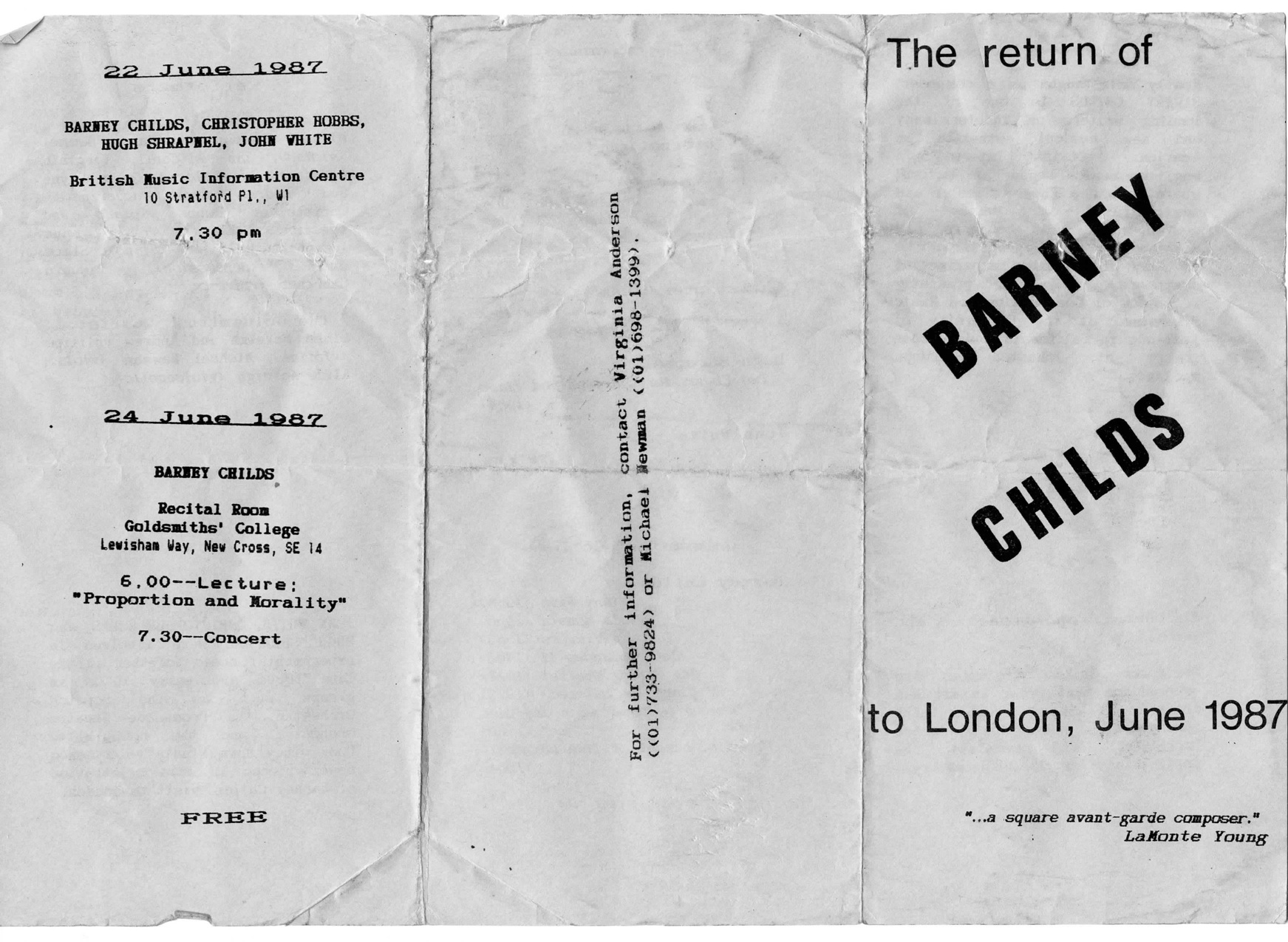

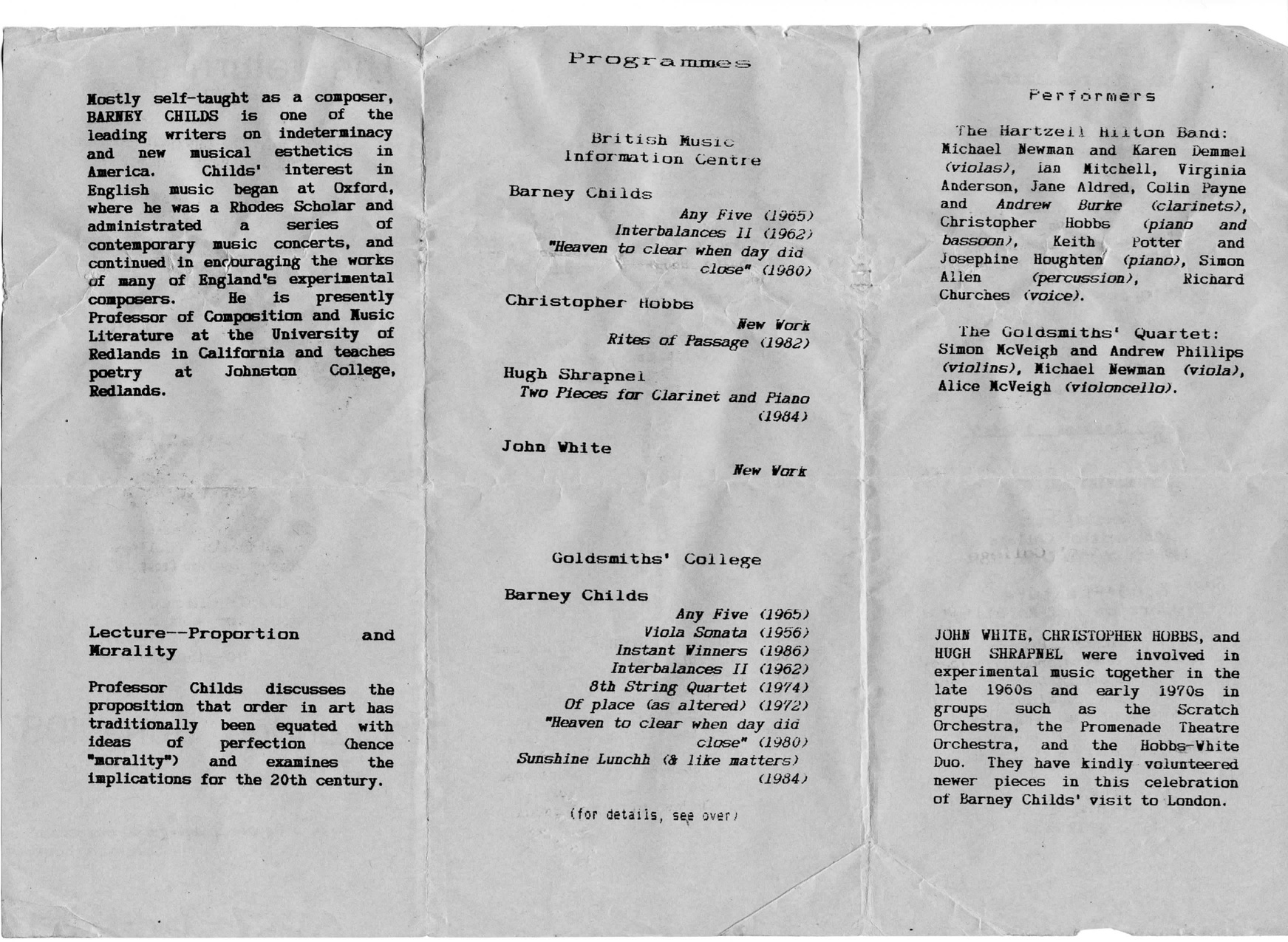

Two days of fun and games at the Union Chapel, which has become the modern era home of the GL. I played in the first complete performance at the UC for the Almeida Festival, July 1984; filmed parts of the GL at the UC for Phillppe Regniez’s Cornelius Cardew biography in 1985, and Chris and I played P. 6 for the Almeida there in the late 1990s. Here we go again— hope to see Brit friends there!

Can’t find the low Ab extension for the bass clarinet…. It’s a cardboard tube, about three feet long. Sits in the bell. But aside from a pencil mark saying something like ‘Ab for P3’, it looks like trash. Hope I didn’t throw it away.

and

I’ve been practicing the Dumbshow, the first part of Paragraph 5 of Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning, using Michael Parsons’ filmed performance to help me learn it (link to this film on our blog entry). It’s like doing slow and pretty aerobics.

and on the EMC Blog:

What are we doing today? Well, in part we’re practicing the gestures for the Dumbshow for Paragraph 5 of Cardew’s The Great Learning, which will be performed Sunday, 12 July, at the Union Chapel, Islington (http://store.unionchapel.org.uk/events/11-jul-15-the-great-learning-by-cornelius-cardew-union-chapel/). The Dumbshow opens Paragraph 5, the longest, most multipart, and busiest Paragraph of The Great Learning. This opening consists of mimed gestures inspired by Native American sign language. The idea is for the slowest performer to start the first sentence, ‘teaching’ it to the next slowest, who then teaches it to the next and so on. One they have demonstrated the first sentence, each performer moves on through all seven sentences themselves.

Is anyone taking part in this paragraph, and if you are, do you have any questions about the score, which describes but does not depict the gestures. If so, in 2003 Christopher Hobbs and Martin Shiel filmed Michael Parsons, one of the founders of the Scratch Orchestra, performing the Dumbshow, and then all alternative gestures that Cardew provided. We’ve put this film up on the EMC site: http://www.experimentalmusic.co.uk/emc/Dumb_Show.html (it takes a while to load — please wait).

You don’t have to do exactly the same gestures that Michael does; reading and following Cardew’s description is enough. But When I was writing about the notation in The Great Learning I found that some of the descriptions are confusing. That is why I asked Michael to film his performance, and for Chris and Martin to film him. Use this as a guide — or just look at the beauty and dignity of Michael’s performance. I hope to see you at the concert!

21 June:

My never-fail low A-flat tube is lost, presumed missing. This cardboard tube, which wedges into the bell of the instrument, lowers the fundamental B-flat to Ab, the drone note for Paragraph 3 of Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning. I therefore auditioned another tube today on my bass clarinet. Soon after, Eri-the-cat was sick in the hall next to the music room. Related occurrence, or sheer coincidence? Discuss.

(in a further discussion): There was that CIA experiment with extreme subharmonics, the so-called ‘brown noise’ because it elicited the loosening of bowels. Perhaps the Ab is the cat barf noise.

25 June:

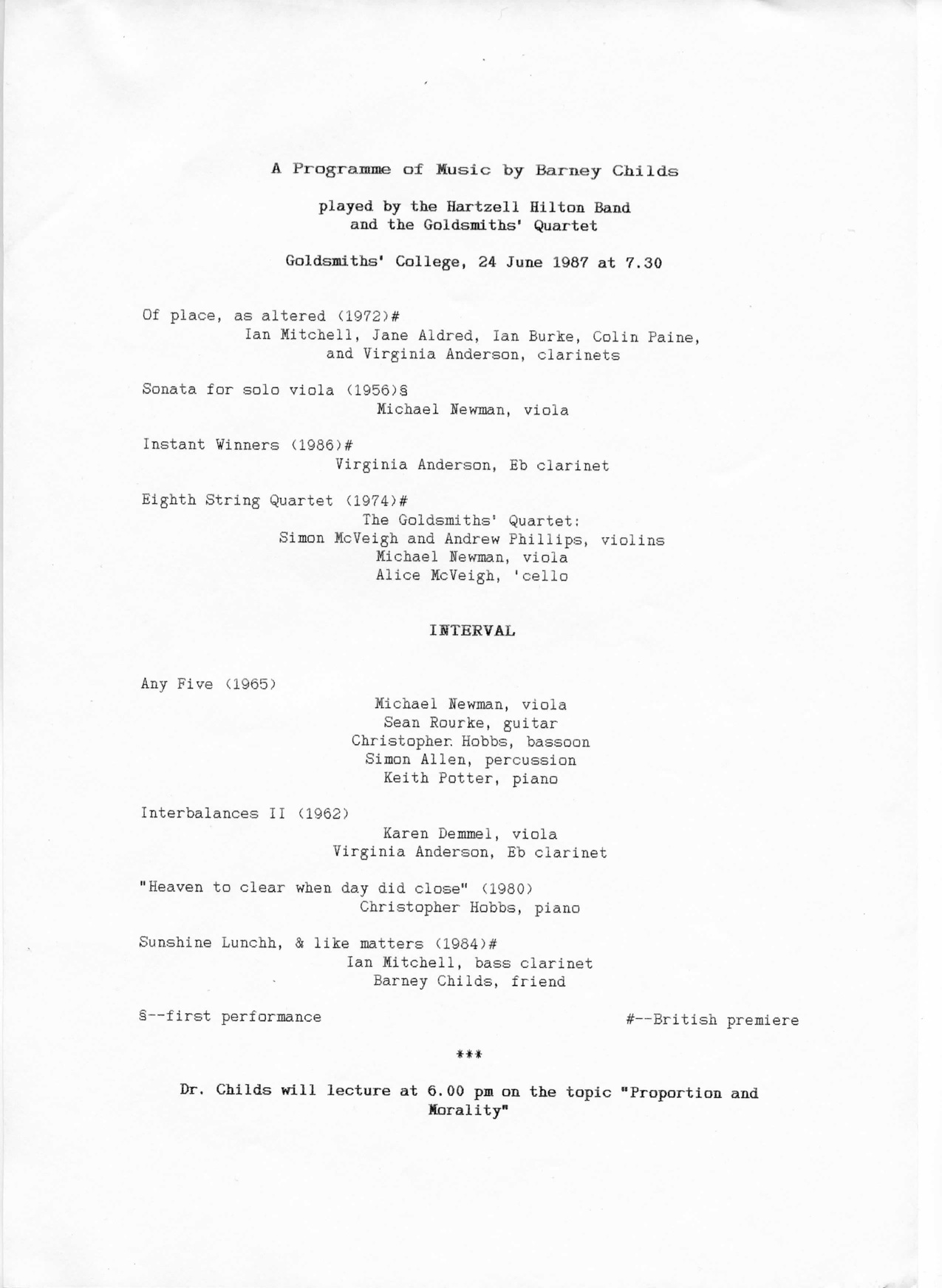

TBT: Well, I know what I’m doing for the Union Chapel performance of The Great Learning on 11 and 12 July, and so what instruments I need.

Paragraph 1: speaking and whistle solo

Paragraph 2: singing

Paragraph 3: bass clarinet with low A-flat extension (drone group)

Paragraph 4: cushion, wand, and guero. (This is going to be fun. I have never played P 4, so I muscled in on Dave Smith’s CoMA (Contemporary Music-Making for All) ensemble. Should be a blast.

Paragraph 5: Dumb Show and whatever else they want me to do. I’m up for it!

Paragraph 7: singingThat leaves out P. 6, which is being done by a student group from Goldsmiths. As many times as I’ve said that this needs a small, bespoke group, with NO show-offs, I’m going to miss doing this sweet, fragile piece for the first time ever. So here’s a clip of P. 6 from Philippe Regniez’s film, Cornelius Cardew, filmed in 1985 in the Union Chapel. At about 43 seconds in, you can see a girl with unfashionable flares, a hippie quilted jacket, and dark glasses. Me.

Cardew, P.6, The Great Learning, 1985

June 30:

Possible whistle for The Great Learning.

6 July

People who think that you just go in and do what you want with The Great Learning will come to grief. A confident performance takes preparation and planning. Thus far today: score for The Great Learning has been organised. P1 whistle solo practiced; stones from 1997 South Bank performance found. Practiced low A flats on the bass clarinet (with the new Ab extension tube) for P3. I also ordered back-up and replacement reeds, as the present reeds will be exhausted by all those drones. Next: practice Dumb Show performance and warm up voice for various paragraphs. Pictured: Possible instrumentation (wand, sonorous substance, guero, and rattles) for P4.

[loads of discussion of what a momentous piece it is]

Part 2 will follow….