The end of September brought a couple interesting events, and some new additions to the Experimental Music Catalogue. The EMC additions include our new Bandcamp page, where you can download new and archival music; another addition is yet to be announced. But the events were coming thick and fast — so thick and fast that we were unable to attend the Fifth International Conference on Musical Minimalism, called ‘Minimalism Unbounded’, in Turku and Helsinki, Finland. I was unable to attend this conference because it overlapped with two other events that week. For the Finnish conference, the best reporter is always Kyle Gann, who has written. ‘Postminimalism Takes Finland’, in his Postclassic blog, here: http://www.artsjournal.com/postclassic/2015/09/postminimalism-takes-finland.html . And I will get to the second event I attended, a two-day study conference at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent on Christian Wolff, with Wolff himself in attendance. But I want to talk here about a grand day out in London.

The first event in this very busy period was a study day, ‘Transatlantic Encounters’, as part of the Minimalism Unwrapped concert series at Kings Place, London. Howard Skempton was the very delightful host of the proceedings, which included a kind of additive panel of delegates: Christopher Hobbs, Sarah Walker, and finally Colin Matthews. The title, ‘Transatlantic Encounters’ may have been made up by the organisers of this event, but it reminds me of a night in London in 1970, in which Gavin Bryars invited Steve Reich to visit the English experimentalists. It was held in a large house in north-west London, in a room that Chris Hobbs had sublet because it was the biggest. Reich played a recording of Four Organs (1970); Bryars played the overture to William Tell, played by the ‘world’s worst orchestra’, the Portsmouth Sinfonia, a group of arts students and others who played instruments with which they were unfamiliar. For me, this 1970 transatlantic encounter says a lot about British experimental and minimalist composers and their American ‘cousins’. It was an encounter that showed off their differences as much as their common interests. And this difference kept wafting about throughout the day’s discussion.

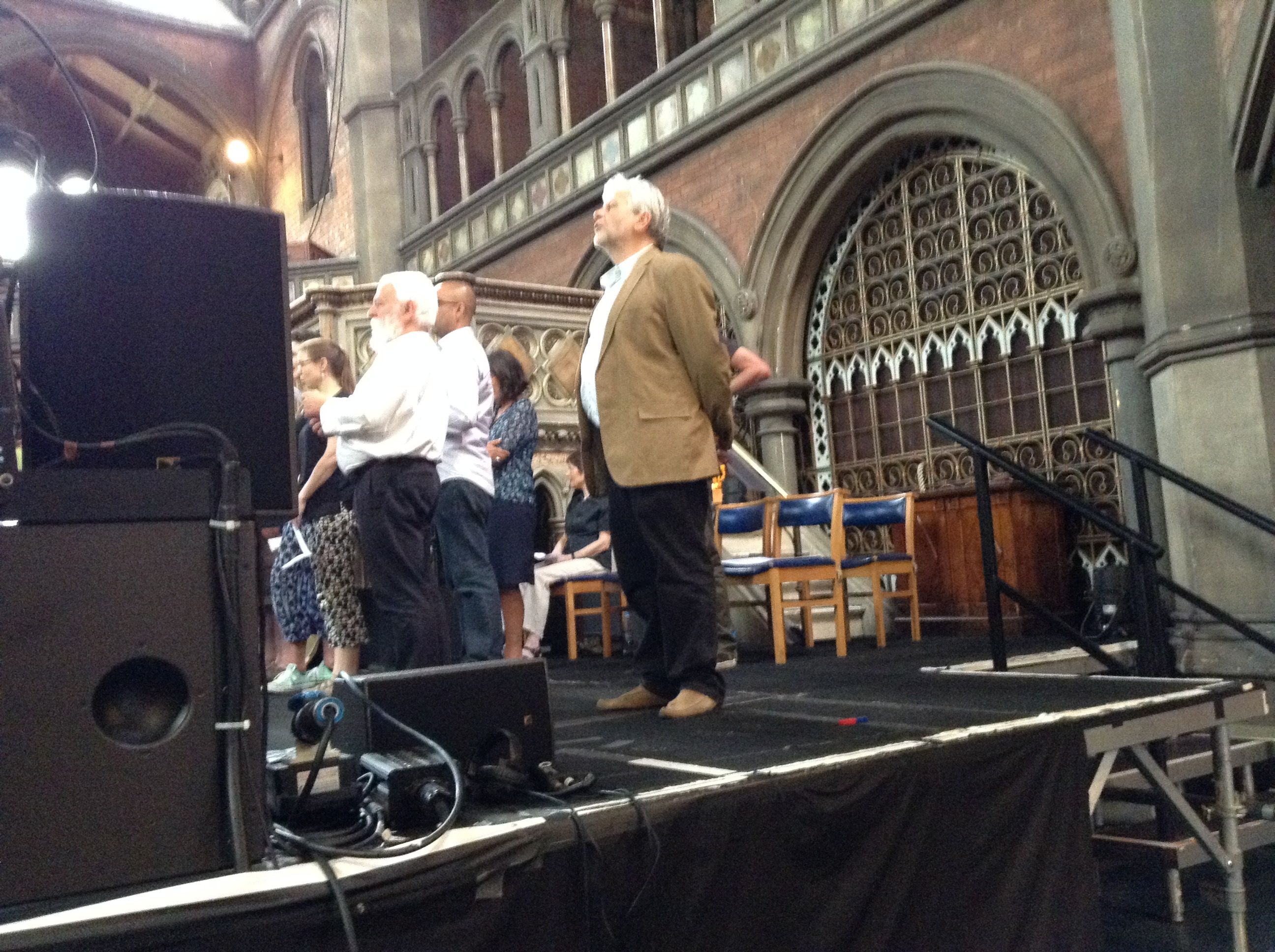

Howard Skempton, welcoming everyone to the study day

Howard Skempton began with an introduction to the movement and his own style, which of course included the work of Morton Feldman and Anton Webern (the former for the feeling and thinking behind this kind of ‘slow, sparse’ minimalism). Chris Hobbs played Terry Jennings’ Piano Piece 1: Winter Trees (1965). Jennings, a friend of Young who died in 1981, is less well known than Young, but his use of stacked harmonies offer a close tie between the American minimalists and the British ones. (For those with access to the journal American Music, I highly recommend Brett Boutwell’s article, ‘Terry Jennings, the Lost Minimalist’, in the Spring 2014 issue. And Winter Trees, transcribed from Jennings’ manuscript by Chris Hobbs, appeared in the EMC’s Keyboard Anthology in 1972). And although Riley, Reich, Glass, Young, Feldman, Adams, and other American minimalists were mentioned, the Brits were, for once, the main act in this day’s discussions.

Howard set the tone for the day’s proceedings: friendly and slightly meandering, flowing from one topic to another as he, and the audience took them. Referring to La Monte Young’s famous Composition #10 (to Bob Morris), which reads, ‘Draw a straight line and follow it’, Howard said, ‘I’m trying to draw a straight line [of argument] and follow it, but it’s an English straight line, which wiggles about a bit’. The audience was free to take part, to ask questions and to contribute. In fact, Howard asked all members to introduce themselves, so that they could chat during the coffee break and lunch. This was both endearing and useful: participants included former Scratch Orchestra members (such as the composer Richard Ascough), members of the nationwide arts organisation Coma (Contemporary Music for All), visual artists, university professors — even a man who had sung in the premiere of Britten’s War Requiem.

Christopher Hobbs and Howard Skempton in the second session

The second half before lunch brought Chris Hobbs to the podium. Chris talked about his work with the Promenade Theatre Orchestra and the Hobbs-White Duo — two groups that brought a specifically English type of minimalism, variously called Machines and systems, to the table. He also talked about minimalism’s honoured ancestor, Erik Satie. Satie’s Vexations, a short piece that can be played 840 times, is a classic minimalist forebear, but Chris played instead a short excerpt from Le fils des étoiles, Satie’s longest written-out work, written for a Rosicrucian play of the same name in 1891. The Preludes to each act are in publication and are performed regularly, but Chris edited the whole piece from the manuscript. He played for us the opening of Act I, which had remained unheard since its premiere until Chris performed it in 1989. Le fils des étoiles is, by every definition except for its age, a minimalist piece, presenting and repeating thematic material without climax, without drama.

Sarah Walker, on the English experimental tradition

After lunch, Sarah Walker gave what was the nearest we had to a formal presentation, providing further information on British contemporaries in the English Keyboard School, including Dave Smith and Hugh Shrapnel. In 1995, Sarah’s excellent PhD thesis was on the English Experimental Tradition, particularly keyboard music. But she did not begin with piano music, rather, the antics of the early Live Batts!!!, which began as a duo of John White and Chris Hobbs in about 1990, using battery-operated portable synthesizers and amps. This continued Chris’s discussion of PTO and Hobbs-White, particularly the use of what were essentially toy instruments (for the PTO, toy pianos and reed organs) or the preference for piano four-hands, a cheap, often domestic alternative to piano duos. Sarah and Chris played one of these pieces by John White, a lovely performance. It would be nice to hear the two of them perform at greater length. However, what struck me about Sarah’s talk was her emphasis on the English Keyboard School, and all of British experimentalism as a community, or even closer, as family. This metaphor strikes me as particularly apt and may go some way to explain the association of people in Nyman’s Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond better than a normal linear heritage could do. Families (or communities) have shared values and experiences that lie at the heart of what they do, no matter how different they may be in daily life. Similarly, Skempton, Hobbs, White, Michael Parsons, Hugh Shrapnel, Gavin Bryars, Dave Smith, Michael Nyman, Brian Dennis, and other composers may compose differently, form different ensembles, work with different artists outside of the core group, and yet there is that familial tie of experience that acts as a shortcut in their own interactions. There is less to be said because they know each other so well….

Colin Matthews’ session (this is beginning to be a visual additive system…)

Finally, Colin Matthews offered a counterbalance from the world of composition outside of minimalism, in terms of his own pieces that may have been informed by minimalism. Howard had intimated that Colin would act as a kind of devil’s advocate, but when I asked him if he was going to argue against the others, he delightedly denied that he would do so. He was, as the others were, jolly and generous. The only general negative he had was for some of the music of Glass, Reich and Adams, and counterposed two of his pieces against American minimalism. But these two pieces actually seemed to me to have more musical links to the Americans than to the Brits: one had a gamelan-like quality; the other seemed to progress and process in a similar way to John Adams’ music of the same time.

Chris Hobbs and Sarah Walker enjoy the canalside autumnal sunshine during the first break

The day seemed to be over before it began. Although the actual meeting was situated in a basement meeting room, the breaks were generous and the fine weather allowed us to enjoy sitting canalside, where the discussions took on an almost holiday atmosphere. The only disappointment was that Howard Skempton, wiggling his straight line about a bit, did not leave time for an examination and discussion of his own music, particularly his Waltz (1970). Michael Nyman saw this piece as something new and important, in Experimental Music: it was ‘the first tonal piece to be conceived in terms of a connected melodic and harmonic sequence — a new tonal “language”…. This is a tonality even more devoid of drama and surprise than Satie’s’ (Nyman, 1974, p. 145). Chris Hobbs, who had performed its premiere, was promised to perform it here. It would have been wonderful to see, after all this time has passed, whether Waltz could still wow the audience with its sheer white not simplicity. But the time, alas, ran out. And the next day, I left for Kent, to catch the Eurostar for Brussels, then Ghent….

Richard Ascough (composer, former stalwart of the Scratch Orchestra), Howard Skempton, and Colin Matthews at the canalside lunch